In the 1970s archaeology took off in Britain. Field teams working on motorway construction projects, such as the M5 in Gloucestershire and Somerset, showed that ancient sites were much more prolific across the countryside than had previously been appreciated. The mapping of aerial photographs, especially in river valleys such as the Thames, Nene and Warwickshire Avon, revealed continuous, overlapping prehistoric, Roman and medieval landscapes. In gravel quarries, as well as historic towns, archaeological excavations increased in size and complexity to mitigate the scale of destruction.

In comparison funds for research into protected sites were more limited. The National Trust set up its own archaeological team, responsible for recording properties, and established a Sites and Monuments Record – now known as Historic Environment Records. The White Horse had been scheduled as an Ancient Monument in 1929, but by the 1970s its surroundings were scarred by erosion, ploughing and over-grazing. After the Rt Hon David Astor donated the land surrounding the WHite Horse to the National Trust in 1979, renewed research became possible.

The initial surveys, starting in September 1980, aimed to tackle these questions. The National Trust and English Heritage were initially reluctant to allow excavation into the Horse itself, as the general belief was that the figure was formed by clearing turf and exposing the underlying chalk. So there should be no stratified layers, with artefacts, or opportunities for dating. Therefore it seemed that excavations would not result in more advanced understanding about the White Horse.

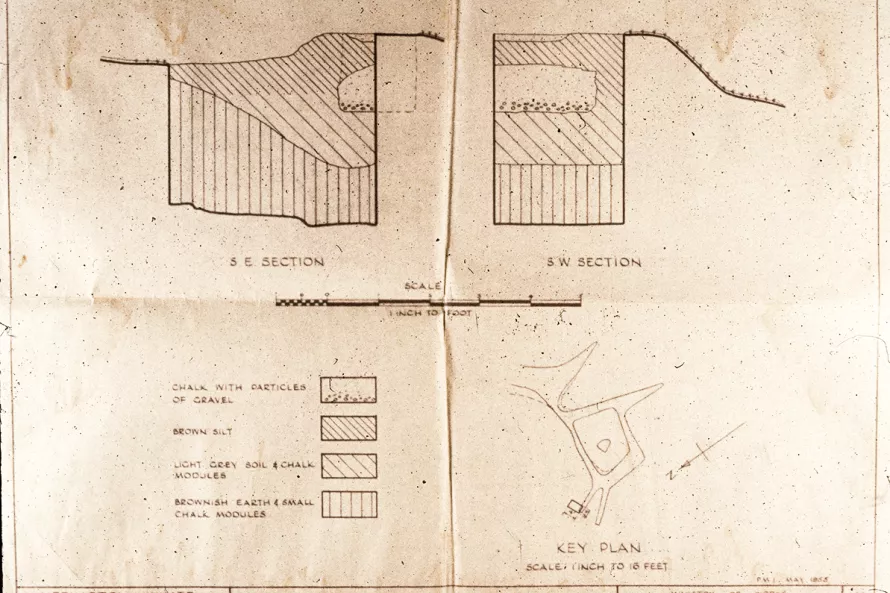

Attitudes changed dramatically when we discovered long-ignored files in the Ministry of Works archives in London’s Elephant and Castle. Here were some very fine drawings and plans illustrating a forgotten excavation into the White Horse. This had taken place after World War II, when the Horse (and other hill-figures) had been covered over to hide it from German aircraft. It seems that during the restoration in the early 1950s a trench had been dug into the Horse’s beak. The section revealed successive layers of chalk in a trench about one metre deep. So the Horse had been constructed and had clear stratigraphy.

So why dig?

Surprisingly, not everyone likes archaeologists. In 1988 Richard Ingrams, of Private Eye magazine, produced an excellent book of artists’ work entitled The Ridgeway: Europe’s Oldest Road; in it, he railed against spoilsport archaeologists, ‘so-called experts’ who tried to dig up the facts. He was not the first to take this line: Oscar Wilde declared ‘where archaeology begins, art ceases’. Of course, we did not agree with these statements: we believe that archaeological investigation does not take the wonder out of the White Horse or any other monuments and features.

The National Trust believed that this evocative place should be enhanced and agreed that archaeological investigations would be an important part of of the restoration to improve White Horse Hill for visitors, but also for biodiversity (insects, birds, flowers). The intention was for the dead in the barrows to remain undisturbed while orchids bloom and the song of skylarks returns.

Through the 1980s work proceeded slowly and carefully, with aerial and geophysical surveys. Small trenches established the position, character and re-use of prehistoric burial sites. We left the burials where we found them to respect the wishes of the ancestors.

Gary Lock and Chris Gosden from the University of Oxford joined us, with their students, to investigate Uffington Castle and other features around the hill. They also excavated neighbouring hillforts: at Segsbury to the east and Alfred’s Castle to the west, revealing the different character of these places.

To protect the White Horse we limited the extent of the excavation and positioned the trenches to investigate specific aspects:

- Re-open the 1950s trench in the beak to see if the plans we had discovered were accurate. They were, confirming that the Horse figure was not scoured into natural chalk. A horse-shaped trench had been dug, probably with bronze or iron tools, with spoil carried in baskets. Fresh chalk was then put into the trench, and over generations layers of new chalk were added. The investigations showed that the beak was an original feature, as was the sinuous segmented shape. We disproved the Woolner theory of a larger ‘natural’ horse. The Horse had shrunk a little, but also the plane of its body was, originally, at a steeper angle. So the hill-figure was once more visible to observers in the Vale.

- Find evidence to attempt to date the Horse. The delays in the fieldwork meant that by the 1990s an important new method of dating was available – Optical Stimulated Luminescence (OSL). Archaeologists often rely on material evidence like pottery, coins or other artefacts, to date sites. Radiocarbon samples can be taken from organic material such as bones. None of these things were found in the layers of the Horse. OSL samples can, however, be taken from buried silt, containing minerals such as quartz and feldspar.

The samples taken from the White Horse was the first time that OSL dates were obtained from an archaeological site in Britain, by the Oxford Lab. These dates are not very precise, spanning between 1380 and 550 BC, however, they indicated that the Horse had been created around the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age, about the same time as the hillfort was built.

Who made the Horse and why?

There was no dense population living in Uffington Castle. We do, however, know of contemporary farmsteads, of thatched round houses surrounded by fields, scattered across the Downs and the Vale. These communities probably came together to build the hillfort, and the Horse figure and hold regular festivals. They were skilled farmers and metalworkers and probably probably spoke a form of Celtic or Gallic (although they left no written evidence). Genetic evidence points to immigration from Europe and Asia at this time.

In this period the horse, for riding and to pull chariots and carts was imported from the Continent. These animals transformed society and the economy, making a mounted aristocracy possible, transforming travel and becoming an important element in religion. We can see similar impacts on the steppes of Eurasia, in China and, later, across the Plains of America.

Scholars have recently argued for the astronomical significance of the Sun Horse – drawing the sun across the sky or acting as an astronomical marker. It is easy to see the connection to this theory when witnessing the sun rising over the body of the White Horse and flooding the Hill with light.