In February, through the highlights from OA's history we celebrated World Wetlands Day with one of OA's historic projects, the North West Wetlands Survey and looked at an eggcellent find from Roman Buckhinghamshire. We then travelled from Cambridgeshire to Egypt through a beautifully decorated, Nile-inspired keyhandle fromt he Roman period and ended with a visit to a rare Viking-age cemetery in Cumbria.

Exploring the wetlands of North West England

In the 1990s, Historic England commissioned a survey of all the lowland wetlands in Cumbria, Lancashire, Greater Manchester, Merseyside, Cheshire, Shropshire and Staffordshire. These are thought to contain around 37,000ha of peat, more than in the whole of the east of England. Wetlands provide an immensely valuable carbon repository, as well as important information about the past environment and its changes; including human activity, since the last Ice Age. However, threats from construction, agriculture, forestry, and refuse disposal have led to huge reductions in their size.

Our work involved desk-based research about the wetlands and any archaeological finds reported from them, and walking over as much of each wetland as possible, noting the extent and condition of the peat and organic soils, as well as surface finds. Peat deposits were also extensively sampled, by taking cores, which were examined for pollen and macrofossils. Coupled with an extensive programme of radiocarbon dating, these provided information on the changing environment around each wetland, and how they developed, often from multiple small bogs.

Most of the wetlands had been cut over the centuries, to provide fuel for the surrounding population, so that only prehistoric levels survived, but a few examples of ‘topmoss’ -or peat that had never been cut- were found. A north Lancashire example contained evidence for the eruption of the Hekla volcano in Iceland, dating to the Bronze Age (mid-third millennium BCE). This could be connected to climate change, in the form of increased flooding. In Cumbria, the heads and hooves of two cows that had been pole-axed were dated to the early medieval period (seventh to tenth centuries), providing a fascinating glimpse of ritual activity, as only parts of the bodies had been left in the middle of the bog.

Roman eggs in Buckinghamshire

One of our most extraordinary finds was discovered in 2010 at the site of a Roman roadside settlement at Berryfields just outside Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire. Preserved within the wet, muddy layers of what had been a well or waterlogged pit used for malting and brewing were four chicken’s eggs.

One egg had broken in antiquity. The remaining three eggs were whole on discovery but were extremely fragile, with two eggs cracking (and emitting a sulphurous aroma) on exposure to the air. However, thanks to the great care taken by one of the lead archaeologists on the site, the fourth egg was retrieved intact. The eggs are a genuinely unique discovery. Though Roman eggshell fragments, and even complete eggs, have been found before now, this is the largest group of complete eggs known in Britain.

In the Roman period, eggs had all sorts of symbolic meanings. They were associated with the gods Mithras and Mercury and had connotations of fertility and rebirth. Tellingly, where eggshell fragments have been found in Britain, they have usually been found in graves.

The eggs at Berryfields, found with other well-preserved and unusual objects, including complete pottery vessels, a wooden breadbasket, wooden tools, leather shoes, coins, and a millstone fragment, almost certainly represent offerings of some kind. They may have been a votive offering or possibly had been placed in the pit as part of a funerary rite. We can imagine the eggs being carried along the Roman road (known today as Akeman Street, whose route is in part followed by the modern A41) within a funerary procession. As the procession stopped at the pit, a religious ceremony took place, the food offerings being cast into the pit for the spirits of the underworld or in the hope of rebirth.

The archaeological work was carried out for the Berryfields Consortium, a consortium of three development companies, Taylor Wimpey, Kier Living and Martin Grant Homes. The story of the excavation and its discoveries is presented in a book published by Oxford Archaeology: Berryfields: Iron Age Settlement and a Roman Bridge, field system and settlement along Akeman Street near Fleet Marston, Buckinghamshire, by Edward Biddulph, Kate Brady, Andrew Simmonds and Stuart Foreman.

From Egypt to Godmanchester

In 2007, our Cambridge office (then CAM ARC) discovered an unusual Roman key handle in the centre of Godmanchester – Durovigutum – a Roman small town that lies on Ermine Street near the River Ouse, just to the south of Huntingdon. The handle, which is of zoomorphic form, was found alongside 2nd-3rd century AD pottery in an otherwise unremarkable boundary ditch in a very small excavation trench close to the central crossroads of the Roman town. Various possibilities for the creature depicted on the handle were suggested, but the animal is probably a Nilotic beast. It is almost certainly of continental manufacture, and the animal may be very loosely based (perhaps at several removes) on an Egyptian prototype; it cannot be defined as representative of any one particular Egyptian deity.

Apotropaic animal images were often used on key handles, with lions, other large felines and rams being most commonly depicted, no doubt chosen as symbols of strength and aggression and also for their otherworldly powers, providing security above and beyond the simply practical aspect of turning a key. In terms of the Godmanchester handle it is deliberately intended to be strange in the context of the northern Roman empire.

The long jaw and nostril slits of the creature on the Godmanchester handle could be seen as crocodilian, and the unusual ring-and-dot ears are a fair match for those of the crocodile, which has mere oval flaps of skin lying behind the eyes. The lateral grooves of the creature’s skin also resemble the banded scaly plates of the Nile crocodile. Representations of Nilotic creatures such as the crocodile, hippopotamus and mongoose are either very rare or even unknown in Roman Britain.

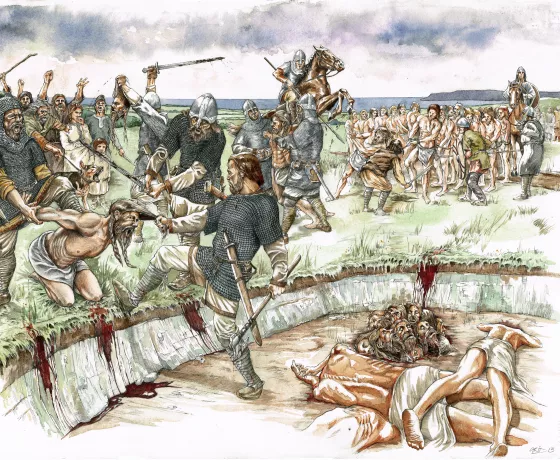

The Viking-age cemetery at Cumwhitton, Cumbria

In 2004, our Lancaster office excavated one of the most important early medieval sites in the North West: a cemetery of six richly furnished burials dating to the early tenth century. Any furnished graves of this period are very rare in England, only about 30 having been excavated, mainly by antiquarians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and cemeteries are even rarer.

The people buried were probably two women and four men, although the bodies were only seen as shadows in the sandy acidic subsoil. One grave contained two oval brooches, characteristic of female dress, and the presumably male graves all contained weaponry, such as swords and spears, with all the graves producing evidence of clothing and other personal items, such as jewellery, combs, and drinking horns.

The modern techniques used to excavate these burials have produced amazing results, such as imprints, in the corrosion on metal objects, of textiles, leather and even seal skin, and have helped to understand better what had been found in other burials by antiquarian excavators. The grave goods came from a wide area of Scandinavia and Britain, and have provided a fascinating insight into the links with the wider world such communities in Cumbria had. The burials took place over only a generation or two, perhaps because this family had converted to Christianity by the middle of the tenth century.

Other posts in this collection

Read the latest posts celebrating our 50th year in archaeology.