So why dig?

Surprisingly, not everyone likes archaeologists. In 1988 Richard Ingrams, of Private Eye magazine, produced an excellent book of artists’ work entitled The Ridgeway: Europe’s Oldest Road; in it, he railed against spoilsport archaeologists, ‘so-called experts’ who tried to dig up the facts. He was not the first to take this line: Oscar Wilde declared ‘where archaeology begins, art ceases’. Of course, we did not agree with these statements: we believe that archaeological investigation does not take the wonder out of the White Horse or any other monuments and features.

The National Trust believed that this evocative place should be enhanced and agreed that archaeological investigations would be an important part of of the restoration to improve White Horse Hill for visitors, but also for biodiversity (insects, birds, flowers). The intention was for the dead in the barrows to remain undisturbed while orchids bloom and the song of skylarks returns.

Through the 1980s work proceeded slowly and carefully, with aerial and geophysical surveys. Small trenches established the position, character and re-use of prehistoric burial sites. We left the burials where we found them to respect the wishes of the ancestors.

Gary Lock and Chris Gosden from the University of Oxford joined us, with their students, to investigate Uffington Castle and other features around the hill. They also excavated neighbouring hillforts: at Segsbury to the east and Alfred’s Castle to the west, revealing the different character of these places.

To protect the White Horse we limited the extent of the excavation and positioned the trenches to investigate specific aspects:

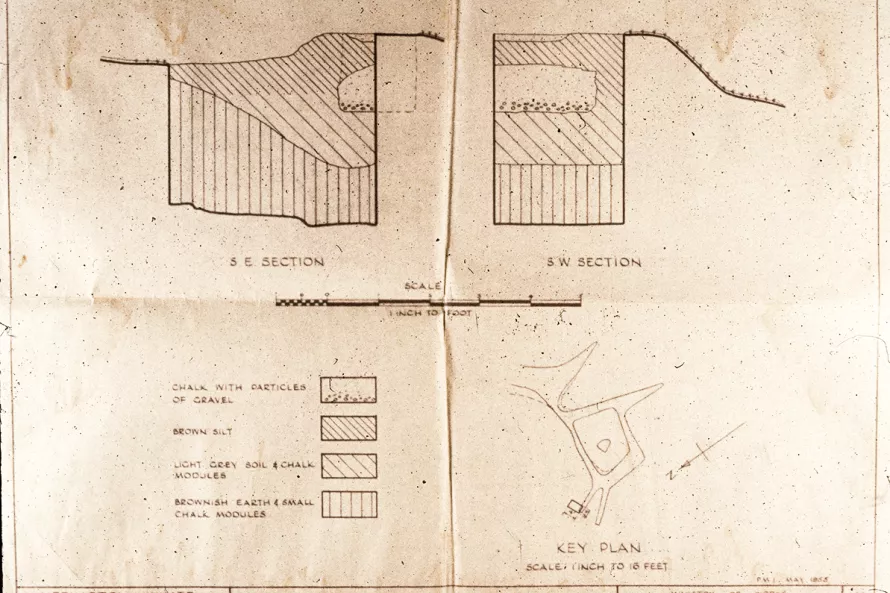

- Re-open the 1950s trench in the beak to see if the plans we had discovered were accurate. They were, confirming that the Horse figure was not scoured into natural chalk. A horse-shaped trench had been dug, probably with bronze or iron tools, with spoil carried in baskets. Fresh chalk was then put into the trench, and over generations layers of new chalk were added. The investigations showed that the beak was an original feature, as was the sinuous segmented shape. We disproved the Woolner theory of a larger ‘natural’ horse. The Horse had shrunk a little, but also the plane of its body was, originally, at a steeper angle. So the hill-figure was once more visible to observers in the Vale.

- Find evidence to attempt to date the Horse. The delays in the fieldwork meant that by the 1990s an important new method of dating was available – Optical Stimulated Luminescence (OSL). Archaeologists often rely on material evidence like pottery, coins or other artefacts, to date sites. Radiocarbon samples can be taken from organic material such as bones. None of these things were found in the layers of the Horse. OSL samples can, however, be taken from buried silt, containing minerals such as quartz and feldspar.

The samples taken from the White Horse was the first time that OSL dates were obtained from an archaeological site in Britain, by the Oxford Lab. These dates are not very precise, spanning between 1380 and 550 BC, however, they indicated that the Horse had been created around the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age, about the same time as the hillfort was built.