Sited as it is, on the River Eden Carlisle has historically, always been an important place: a regional centre, somewhere to meet-up and a stopping-off point for onward journeys elsewhere. With such a long and rich history, it is little wonder that a wealth of archaeological remains should survive just below the soil of the fields that surround the city – most famously, it is still possible to stroll along the line of Hadrian’s Wall. In Roman times, the wall marked the northernmost boundary of the known world; nowadays, rightly designated a World Heritage site, it draws visitors from all over the world. Yet, this is just the tip of the iceberg and many more secrets of even greater antiquity are there to be found, if one knows where to look.

Between 2008 and 2009, Oxford Archaeology undertook an extensive programme of investigations in advance of the construction of the Carlisle Northern Development Route, Cumbria. The Stainton West site turned out to be exceptional, as it revealed prehistoric remains that date back to the first time the landscape was occupied, about 9,000 – 7,000 years ago, providing evidence for some of the earliest Cumbrians.

Stainton West's finest finds

Earliest Cumbrians at Stainton West

The Mesolithic nomadic hunter-gatherers from Stainton West probably settled here in seasonal camps, perhaps to take advantage of marine and riverine resources, such as migrating salmon. A massive assemblage of struck stone tools, found near hearths on the banks of a relict channel of the river Eden, show where people made their homes.

Large circular cropmarks 150m upslope of the excavations suggest that two henge-type monuments marked this location on the edge of the floodplain as an important place of congregation and ceremony for the first farming communities in the region, about 5,000 – 6,000 years ago. The evidence from Stainton West, as well as from other known sites where similar monuments are present, suggests that people often used wetland and dryland areas in different ways during the rituals enacted there. This may explain the unusual finds within the waterlogged channel deposits. In amongst the remains of a rudimentary wooden platform, a decorated pottery vessel, several pristine arrowheads and four stone axes were recovered, all probably pre-dating the henges. These finds are characteristic of the Neolithic period and three of the axes were made from stone derived from the central Lake District.

Perhaps as much as 1,500 years later still, at the time of the first use of metal, the now silted, channel continued to remain a focus for activity. A collection of fire pits associated with spreads of burnt stone are evidence that social gatherings still took place there, which possibly involved feasting, saunas or the processing of natural resources.

The palaeochannel

The river terrace at Stainton West was sculpted by the glacial channels that laid down the sandy gravel deposits that underlie the site, at the end of the last Ice Age (early-Holocene period 10,300–8,500). As the glaciers retreated, the previously depressed landscape rose, resulting in the formation of a number of terraces which were intersected by channels. The emergence of the palaeochannel at Stainton West developed during the later mesolithic period (or mid-Holocene), and started to infill at the same time that the human activity on site began.

The site appears to have occupied a significant position in the floodplain, where the river potentially narrowed and was constrained by several floodplain islands, which would have possibly facilitated crossing at this point. High points or promontories at the edge of a wetland area would have been very attractive locations for early prehistoric communities to exploit the rich wetland and river resources present. The sequence of deposits forming the Mesolithic organic deposit indicates a shallow channel, which was gradually drying out. Preserved wood in the channel shows that various animals shared this habitat with humans. Tree trunks had been gnawed by beavers and dragged together by them to form lodges.

At various depths within the channel, stone, wooden and ceramic objects were recovered. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the earliest deposits in the channel formed in the Later Mesolithic period (between 9,000 and 6,000 years ago) and the latest during the Late Bronze Age (around 3,000 years ago). The accumulation of the majority of the wood shows that the flow of the river gradually slowed. It is possible that some of the wood recorded could have fallen in from overhanging branches and the river banks, but it is just as likely that some of this wood was deliberately introduced into the channel. A number of gnawed tree trunks and branch ends indicate beaver activity.

Mesolithic communities may have first been drawn to the Stainton West site as a result of localised woodland disturbance caused by this beaver clearance. These environments would have been attractive to hunter-gatherer groups, providing ready-made coppice stems that would be ideal for firewood, arrow shafts or harpoons. The new tree growth would also have encouraged foraging and hunting resources, and the ponding of the watercourse may have provided good fishing. These conditions could have been instrumental in the selection of this particular place for camps or more permanent settlement, resulting in the lithic scatter and features within the grid square area.

Woodworking

Material retrieved from the palaeochannel at Stainton West provides evidence for how wood was worked with stone tools, which can differ from the methods associated with the use of metal ones. Coppicing is an ancient technique of husbanding wood to provide poles of suitable thickness for use as hafts for tools or for use in construction which was already well established in the Neolithic period. Techniques at Stainton West used to remove coppice stems, sometimes used for the manufacture of stakes, included a combination of cutting, tearing, and cross-cutting.

Several chunks of coppice stool in the assemblage possibly provide evidence of the bowl manufacture. Certain other pieces form debris associated with tree felling, involving a technique where parallel grooves were cut into the trunk, with the wood in between then prised out tangentially. This is the first clear evidence that such a method was used in this country.

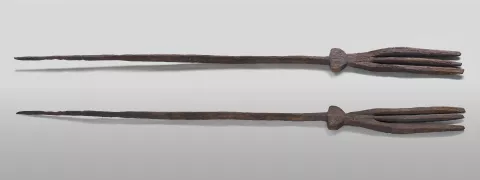

Perhaps the most amazing and unusual woodwork finds from Stainton West are two three-pronged tridents. Radiocarbon-dated to the fourth millennium BC and measuring in excess of 2m in length, the tridents were carefully carved by stone tools from single green oak planks.

Similar artefacts were recovered during the nineteenth century at Ehenside Tarn, near Ravenglass, on the Cumbrian coast, and Armagh, in Northern Ireland, but their function is something of a mystery; it has been suggested that they may have been for agriculture or fishing, although none of the explanations proffered so far seem satisfactory. The tridents and the tree trunk with bear claw marks are displayed in the "Origins: Reimagining Cumbrian Prehistory" gallery at the Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery in Carlisle.

Worked stone

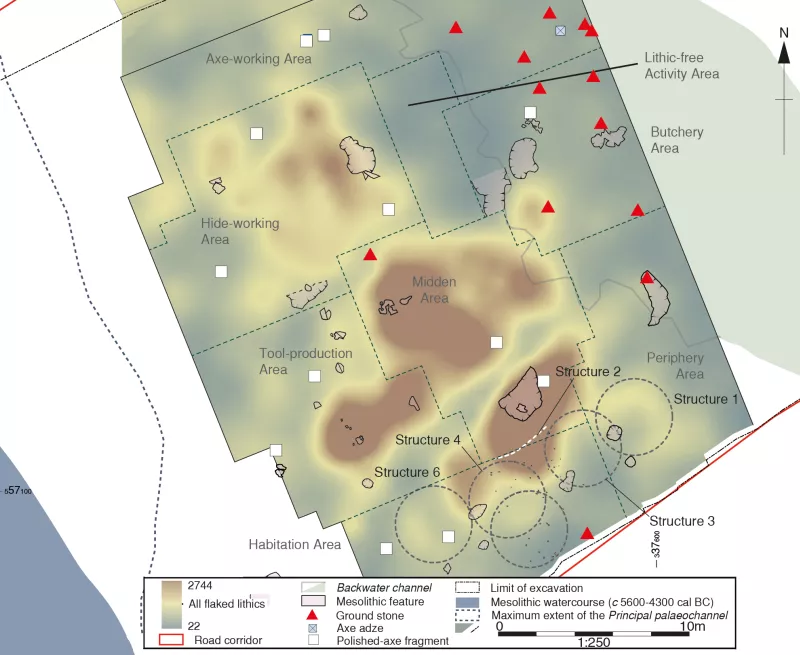

The worked stone assemblage numbered over 300,000 struck pieces, spread over 886 m²

within the site. It was retrieved, in toto, by whole-earth sampling 270,000 litres of sediment, from

a 1 m grid, and by wet sieving this on site through a 2 mm mesh. Features, such as stakehole

structures, hearths, pits and tree throws, were recorded, excavated and sampled for

palaeoenvironmental remains. Radiocarbon dating has shown that the main phases of activity

spanned c 6100 - 1400 cal BC, throughout the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods and into the

Bronze Age. However, it is thought that most of the microlithic-technology finds related to an

encampment that was, probably, regularly and repeatedly occupied, over several centuries, until

the mid-fifth millennium cal BC. Despite organic remains being largely absent beyond the

palaeochannel, analysis of the lithics, including use-microwear, geochemical analysis and

spatial analysis, has been highly revealing, and has demonstrated that the activities undertaken

at the encampment occurred within the same zones over its history. Traditions influencing how

the space was used may have developed as activities were constrained by interactions with both

natural and cultural features, including a midden, the watercourses and woodland vegetation. The lithic materials were procured from many sources, some remote to the site, which, when considered in the context of lithic use in the region, suggest that it lay at the hub of a hunter-gatherer network extending to the west coast and 100 km in other directions. The lithics suggest that the encampment was perhaps associated with catching migrating salmon, probably in the spring/summer months.