Despite the promise of afternoon thunderstorms, the sun persisted in its merciless flare for the opening of the week, after a beautiful weekend. The sun, however, was not the only returning factor; Evan, one of our Graduate Trainees, returned from a week in the office, where he had been working in the post-excavation finds department as part of his training.

Understanding what happens to your finds after they have been excavated and bagged is an invaluable part of being an archaeologist, and one that should not be discounted. Once found, the finds are sorted into bags depending on where they were found and in which soil layer of a feature (be it a pit or ditch or whatever), before being labelled and boxed up to be returned to the office.

Every piece of bone, pot and metal recovered can tell us something about the site. As discussed before, knowing where an artefact comes from (whether a base layer of a ditch or a surface layer) can help us reconstruct the sequence of events, providing vital clues about when a feature was dug, what it was used for and when it was abandoned.

Once the bags of finds make it to the office, they are meticulously cleaned, one of the things our own Evan was learning to do. After this, they are quantified (their weights recorded) and characterised (what they are, date range etc.) This information is included in the first report produced after an excavation finishes, called a post-excavation assessment. This report poses research questions and recommendations for the finds to be fully analysed, which might include specialist procedures like carbon dating or isotopic analysis of bones, or x-rays or illustration of metal objects. It can take a few years to undertake the full specialist analysis and combine all the strands of evidence to understand the story of an archaeological site.

The final report will be submitted to the county’s Historic Environment Record, and the records and finds from Wintringham will be deposited with Cambridgeshire County Council, to be accessible to researchers and the public.

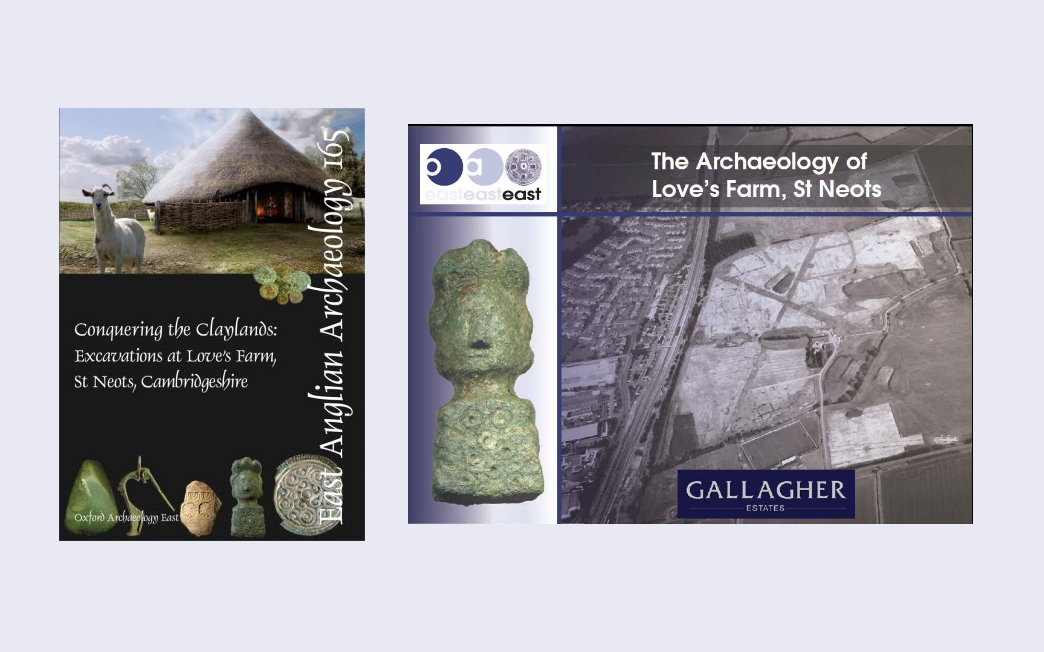

Images of the front covers of publications for the Love's Farm archaeological investigations. (Left) Conquering the Claylands, an academic monograph. (Right) The Archaeology of Love's Farm, a public booklet.

A particularly exciting find this week is that of at least two cremation burials, where the burnt remains of the deceased have been buried in a small pit, about a foot across. As Christians historically do not cremate their dead, this is highly likely to have been the remains of pagan peoples.

However, this only just narrows down our options of date and meaning. The cremation could belong to anyone from early Roman or Anglo Saxon settlers to people of prehistory (bronze age), and so may well be contemporary with the Romano-British (a culture of settled Romans and native Britons) ditches and enclosures. The fact these remains are present suggests a more permanent settlement, where people lived out their lives to completion.

Physically, all that remains (in this case) are small pieces of bone, whitened and crushed by fire and the years to almost indistinguishable objects. However, dignity remains, as well as a responsibility on the archaeologists’ behalf to treat past peoples with the respect they deserve.

This is why every single piece of identifiable human remains must be removed from site, if and when found. For other archaeological features, soil samples are taken in the form of two 10L buckets of whatever we are sampling, usually a particularly burnt layer of earth from a feature; the vast majority of this material is kept in the ground. With the contents of a cremation burial, the whole thing has to be removed and taken to the labs for excavation and analysis.

Nothing humbles the archaeologist in the field or gives them such a sense of connection to the past as the presence of actual human remains, no different from you or I. They were once as you are now, and like them you shall one day become.

Other posts in this collection

Read our latest posts about the archaeological investigations at Wintringham.