December means the conclusion of the #OAat50 highlights series. This was a great year and a great opportunity to revisit some of our favourites and most special sites or finds form 50 amazing years of archaeology. So, the last month needed to be something special! We started with a visit to Norton Abbey in Cheshire, which produces fascinating insights into the both the people who lived and died there during its very long history. Then we travelled to Essex where the OA team found the remains of a rare and extremely fascinating Neolithic monument, a causewayed enclosure. Finally, our 50th highlight was a discovery that made the news in the UK but also abroad: a mass grave by the Dorset Ridgeway. The post-excavation research revealed the decapitated individuals buried there originated from Scandinavia, writing an unexpected chapter in early medieval history.

From priory to family seat

For the first #OAat50 highlight of December we visit Norton Priory in Cheshire.

The Augustinian Priory of St Mary was moved from its original site at Runcorn, to Norton, in 1134 by William fitz William, the Norman Baron of Halton, Cheshire. Despite a major fire in 1236 it grew in size and stature and was granted Abbey status in 1391. Indeed, its Abbot was a senior and much respected member of the Augustinian order.

Like many long-lived monasteries, the cloisters were to the south of the church and both these and the church grew with the prestige of the foundation. It also became the burial place of members of William fitz William’s family, although the principal benefactors were the Duttons, who built a burial chapel on the north side of the nave. At least some of the family seem to have suffered from Paget’s disease, whereby the regenerative process of bone within the body becomes unbalanced and weakens the skeleton.

An early burial in the twelfth century displayed characteristics of Down’s syndrome. He was over 46 years of age and appears to have lived a full life within this community. There was also at least one case of leprosy from the early fourteenth century, in a young man buried in a stone coffin in the vestibule to the chapter house, clearly a prestigious position. He was surrounded by three small stone coffins, clearly for children.

A remarkable survival from the Abbey is the twice life-sized statue of St Christopher, dated to between 1375 and 1400. Conservation has identified traces of the original painted decoration, the Saint once being dressed in a vermillion cloak, with dark grey hair and beard.

The monastery was dissolved in April 1536 by Thomas Cromwell under the orders of Henry VIII, and the site was sold in 1545 to the Brooke family, who occupied the site until 1921. The early Brookes adapted part of the Abbot’s quarters, kitchens, and west range, but in the eighteenth century much of this was demolished and a fashionable classically inspired mansion was built: this was demolished in 1928. The site was excavated in the 1970/80s and there is now an award-winning museum displaying much of the monastic ruins.

A Neolithic monument in Essex

This #OAat50 highlight is a causewayed enclosure, one of only 80 in the whole of the UK. During the summer of 2018 a team from OA's Cambridge office excavated a previously unknown Neolithic causewayed enclosure on land off Gilden Way, Harlow. It was located in a setting that included a possible Neolithic longhouse 450m to the east suggesting that there may have been settlement not too far from the monument. Although causewayed enclosures are still a rare archaeological monument type within Britain, this was located only about 2km from another example at Sawbridgeworth.

A refitting process with all the pottery from the site was carried out togetehr with the Cambridge Archaeological Unit, revealing new information about the site and its use. Watch the video at the link below.

The monument formed a ‘C’ shape overlooking a tributary of the River Stort and was constructed periodically, beginning before 3650-3527 cal. BC (95% probability), with a series of intercutting pits opened during repeated visits to the site. Although the causewayed enclosure was mainly visited during the Early Neolithic, the radiocarbon dates and pottery indicate that there were occasional returns to the site during the Middle and Late Neolithic for the opening of a small number of additional pits. The final pit was opened prior to 3359-3099 cal. BC (95% probability), giving a lifespan of the monument of approximately 300-450 years. Within the sequence of deposits, and focused towards the centre of the monument, were midden-like deposits that were associated with concentrations of pottery and flint.

Enclosed within the monument were two clusters of pits that as well as containing similar pottery and flint to the monument itself contained hazelnuts in two thirds of them and cereal grains in approximately half of them. The form of these pits, and their apparent prompt backfilling, however, suggest that they were not opened for the storage of grain, but as with the monument itself, saw the disposal of material within open features, probably from surface midden deposits.

Overall, the site contained a substantial quantity of pottery and flint (c. 55kg of pottery and c. 7,500 flints) but smaller quantities of other material such as fired clay (287g), burnt stone and a saddlequern. The pottery included a mixture of decorated and plain flint-tempered Mildenhall type, with a refitting exercise carried out that suggested vessels had been broken prior to being burnt and showed rare re-fitting of sherds between the monument and the pits it enclosed. This presence of cups and bowls amongst the pottery suggests that there was consumption taking place in the vicinity, perhaps as ‘feasting’ events associated with some visits to the site.

Although animal bone was not as well preserved, with only 148g recovered, the botanical evidence demonstrated that there was a mixture of agriculture and foraging taking place through the survival of cereal grains alongside hazelnut shells and apple.

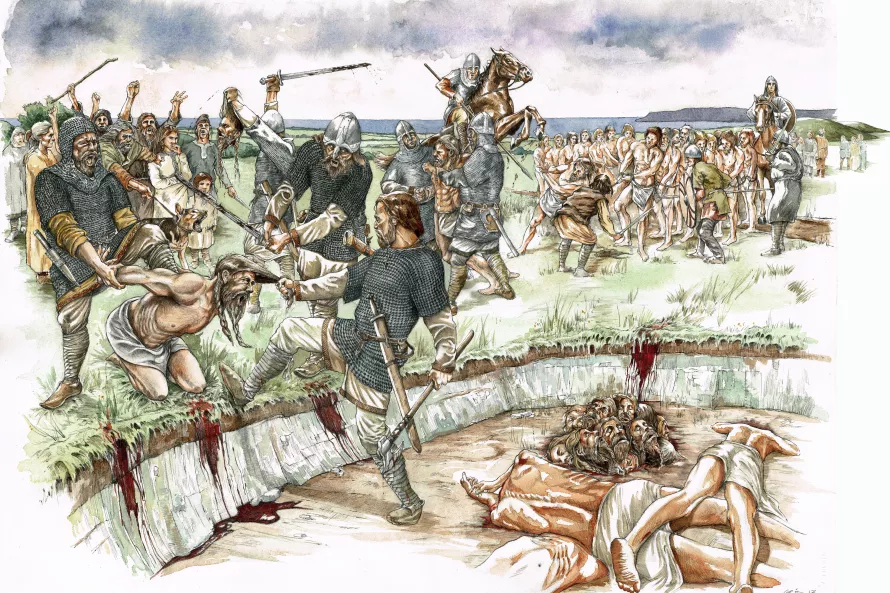

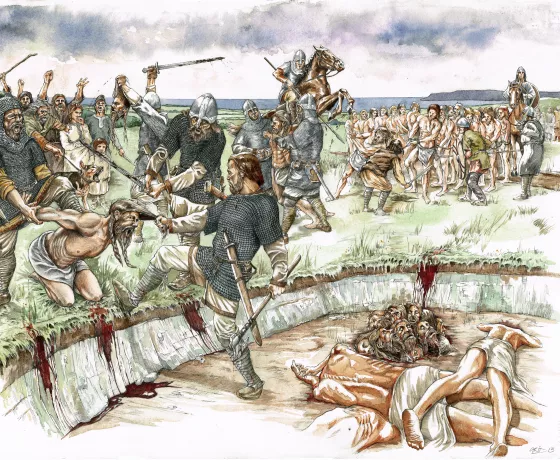

A gruesome end for a group of Vikings

The site featured in this #OAat50 needs no introduction as one of the most dramatic discoveries made in Britain in recent years: around 50 skeletons in a disused roman quarry pit on Ridgeway Hill, Weymouth.

All of the skeletons had been decapitated, their heads placed in a pile located at one edge of the grave, and their bodies thrown into the pit. Analysis proved them to be a mass grave of executed Vikings, dating to the early 10th to early 11th century. Chemical study of their bones and teeth suggested that the men were a disparate group, with many originating from Scandinavia and north-eastern Europe.

The Ridgeway mass grave is arguably one of the most exciting and unexpected archaeological discoveries to have been made in Britain. It has received considerable media attention; has been widely discussed in a wide range of publications; has featured in a major joint exhibition with National museums in Copenhagen, Berlin and the UK and has been the focus of several documentaries. The discovery of the grave was even performed as an opera on stage - The Chalk Legend - by highly acclaimed artists as a trailblazing event for the London 2012 Olympics and Paralympics. Such has been the interest in the grave, that it has become its own fascinating story. This site will no doubt continue to capture minds for decades to come.

The mass grave was a completely unexpected discovery, made in 2009, during the construction of the Weymouth Relief Road in Dorset for the 2012 Olympics by Skanska Civil Engineering, for Dorset County Council. The skulls were the first skeletal remains to be spotted, but at that stage they were presumed to represent a prehistoric or Roman-period funerary context. However, as more bones were uncovered it became apparent that something much more unusual had been found: the skulls were piled on the southern side of the grave and what were assumed to be their articulated post-cranial skeletons were lying jumbled throughout the feature. This was quite unlike any prehistoric or Roman funerary context known from the area, or indeed the rest of the country.

Once the excavation had exposed most of the skeletons, three bone samples were submitted for radiocarbon dating. A weighted mean of the results was calibrated to cal AD 970 – 1025 (SUERC 1045+/-19 BP), showing that the grave had not formed over a long period of time, but represented a single event which had taken place during the early medieval period rather than during prehistoric or Roman times, as initially hypothesised.

Shortly after the excavation, samples from teeth and bones from the skeletons were sent for chemical analysis to examine the origins and migratory histories of the men. Back then, this was a relatively rare technique, but it provided important data on the victims’ backgrounds which would prove to be pivotal to the interpretation of the grave.

Overall, the results indicated a disparate group of individuals, in terms of origin, migration and dietary habits. They had diverse origins, from Scandinavia and the Baltic region, had lived in the Scandinavian region in later life and had not been in the British Isles for long before their deaths.

Analysis of the skeletons provided further clues. Although most of the men were 18-25 years old when they died the youngest was in his early or mid-teens and the oldest, over 50. They possessed features, particularly those relating to height and facial appearance, that were very similar to Scandinavian populations of similar date. Perhaps surprising for a predominantly young group of individuals who had died in their prime of life, the men were not in the best state of health.

The mass grave sits on the crest of Ridgeway Hill next to a Parish boundary and Roman road, near prehistoric monuments and within view of Maiden Castle. There is little doubt that this location was selected to make an example of the individuals buried there.

The circumstances that led to the mass killing and burial of the men found on Ridgeway Hill may never be fully understood but based on current evidence, it seems likely that the context represents a ship’s crew, a Viking raiding party, captured off the Dorset coast.