In September, the #OAat50 highlights explored the early medieval origins of Norwich and the long, complex history of Oxford Castle and its quarter. We looked back at an exceptional dig to bring back to light a Spitfire shot down in the Fens during the Battle of Britain. And we revisited the multi-phase site at Stainton West, Cumbria, where the OA team uncovered traces of gatherings during the Mesolithic.

Writing about early medieval Norwich

OA has an excellent post-excavation and publication team and a great track record of publishing many of our projects for the public. Sometimes we analyse the finds and information from excavations carried out by others.

This #OAat50 highlight is one of these cases. We had the privilege to work on the results of excavations by the Norfolk Archaeological Unit (NAU) in Norwich between 1999 and 2008. We now publish "Aspects of 7th- to 11th-century Norwich", the results of this work focusing on 7th-11th century Norwich.

You can find all the publication's details and read more about Anglo-Saxon and medieval urbanism on the Knowledge Hub at the links below.

Norwich, its castle and cathedral, the medieval cobbled streets are famous all over Britain and beyond. However, its origins, especially its pre-Norman history, were not very well known. This book and the work behind it are special because they bring together the results of 5 excavations that revealed the previously elusive Middle Saxon origins of Norwich.

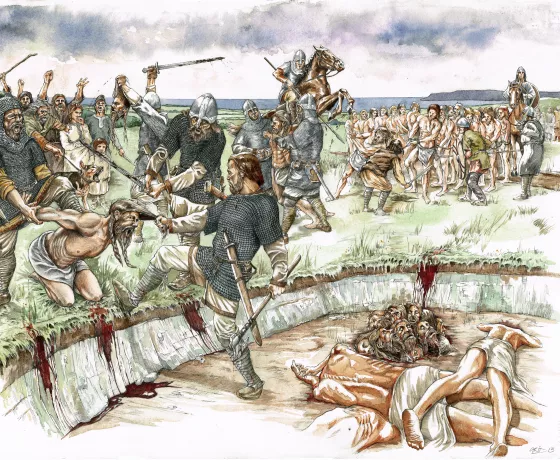

The excavations and the subsequent post-excavation analysis and research work added to previous knowledge about the two fortified settlements which link to the Viking incursions and attacks in the region. These 'burhs' were the beginning of what was an important centre through the Anglo-Scandinavian and Norman periods and beyond.

A Spitfire in the Great Fen

On 15th September 1940, the Luftwaffe launched its largest daytime attack against London, aftre starying its air campiagn agains the UK in July 1940. The aim of the attack was to defeat and destroy the RAF to launch a new phase of the invasion of Britian. The RAF command, however, defeated the attack, also thanks to weather conditions, and lived to fight the long nights of the Blitz. Today the Battle of Britain is commemorated to remember, in Winton Churchill's words, "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few". This week's #OAat50 highlight also commemorates "The Few".

In 2015, during the Rymes Reedbed element of the Great Fen restoration project, OA was required to excavate the remains of a Spitfire, which crashed at Holme Fen in November 1940, claiming the life of pilot Harold Penketh. The excavation was to become a hugely successful partnership involving an array of organisations and groups (20+) including The Wildlife Trusts Historic England the Ministry of Defence, local Great Fen volunteers, local schools and many elements of the wider community, all of which were able to participate in the archaeological excavation. Serving military personnel from Operation Nightingale and the nearby RAF bases at Wittering and Wyton were also part of the dig team and provided a unique insight into a project to recover ‘one of their own’.

The excavation of Spitfire X4593 was also a rare opportunity for a professional archaeological unit to recover a crashed aircraft, and as a result the Great fen Spitfire project will now be used by Historic England as an exemplar on how all future archaeological excavations to recover crashed aircraft will be conducted in the UK. The project has therefore been hugely important for a multitude of reasons, not just archaeologically and to provide information on an important part of the local history but above all of this it was able to provide closure to the family of Harold Penketh, all of whom were incredibly supportive and pleased to see Harold’s sacrifice honoured by so many people.

The project enjoyed International media coverage and was broadcast on the BBC on Remembrance Day Sunday November 2015, and in 2016 a memorial plaque to Harold Penketh was erected on the site. The remains of the Spitfire are currently on display at RAF Wyton but may eventually be on display at the Great Fen.

From Anglo-Saxon beginnings to modern jail

For the next #OAat50 highlight, we go to an iconic Oxford site that was almost next door to our original office in Hythe Bridge Street: Oxford Castle and Prison.

Tom Hassall, our original director, excavated peripheral parts of the castle in the late 60s and early 70s, but it was only once the prison closed in 1996 that the entire site became accessible to anyone other than prisoners or their gaolers, and we were finally able to work inside its walls. In 1999 we started investigations in support of the Oxford Castle Heritage Project, which transformed the site and the old Victorian prison into a hotel, with restaurants, apartments, and a new heritage centre.

You can find more details about this exciting piece of Oxford's history on the Knowledge Hub at the link below

Oxford Castle was built in 1071 at the west end of the thriving late Saxon town, in the classic motte-and bailey form, and was the county castle throughout the medieval period. Largely abandoned by the late 16th century, it continued to serve as the county gaol, with new prison buildings added in the 18th century and 19th centuries.

Our excavations uncovered remarkable evidence of the development of this corner of the town, including sherds of very early Stamford ware pottery, datable to the foundation and earliest years of the burh at Oxford, perhaps as early as the late 9th century. We revealed the 10th-century rampart of the late Saxon town (or burh) and its later facing wall (images 2 and 3), with evidence for re-building likely to be a response to the threat of Viking attacks.

We found burials and two large timber buildings which mean there may have been a high-status residence here in the late Saxon period, perhaps the estate centre of an individual of the rank of thegn, or above. We also showed that St George’s Tower – a massive stone tower that still stands today - may have been part of an associated church at the West Gate of the Saxon town. Late Saxon cellar pits were found that are probably the remains of buildings that were demolished to make way for the building of the Norman castle.

The site is still dominated by the castle’s massive Norman motte. We revealed the foundations of the tower that once stood on top of it, as well sections across the massive bailey rampart, and the deep, waterlogged ditches that surrounded both the motte and the bailey. We also found parts of the castle’s later defensive wall, towers and gates, and buildings within the bailey. The castle was briefly refortified in 1650-51 during the Parliamentary occupation of Oxford in the English Civil War, and some evidence was recovered for the creation of a short-lived gun platform on top of the motte, and a sally port (a secure, controlled entry way) within the western defences.

Between the late medieval period and the middle of the 18th century the buildings of the former castle chapel were used to house the prisoners at the county gaol, and a number of prisoner burials were found in the motte ditch, dating from the late 15th to the 18th centuries. Several skeletons, probably of executed felons, had been dissected (or ‘anatomised’) prior to burial. There was huge excitement at the time of discovery as the burials were linked to the notorious ‘Black Assizes’ of 1577, an outbreak of ‘gaol fever’ (probably typhus) which killed 300 people including the judges, the clerk, Lord Lieutenant, Sherriff, and coroner. A ‘saucy foul mouthed bookseller’ called Roland Jenkes was convicted of the crime of ‘scandalous words uttered against the queen’, and cursed the court, jury and city, apparently leading to the deaths; in reality, he probably passed on the disease having been himself infected in the unsanitary and crowded gaol. He survived to lead a long life as a baker in France.

Purpose-built prison buildings were built in the late 18th century, and we recorded these in in detail, along with the mid-Victorian ‘separate system’ A Wing, which now houses the Malmaison hotel (images 4 and 5).

Notable finds include facetted chalk objects that may have been used in parchment making, and important collections of late 11th- and early 12th-century shoes from the motte ditch. Bird bone from the late 11th-century fills of the motte ditch included crane, partridge, white stork, quail and swan, reflecting the high status of the castle’s occupants.

Before Hadrian's Wall

This #OAat50 highlight is an outstanding site that sheds light on the Mesolithic and Neolithic inhabitants of the Solway area.

Between 2008 and 2009, Oxford Archaeology undertook an extensive programme of investigations in advance of the construction of the Carlisle Northern Development Route, Cumbria.

See more about Stainton West at the links below.

In the course of this work, the team identified and excavated an internationally significant prehistoric remains at Stainton West, near Carlisle, revealing huts, hearths, and a lithic assemblage of over 300,000 fragments. The materials for these objects came from sources near and far, which indicates that the site could have been a hub for hunter-gatherer network that included the west coast as well as territories within a 100 km radius.

Radiocarbon dating showed that the main phases of activity spanned c 6100-1400 cal BC, throughout the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods and into the

Bronze Age. However the lithics evidence identifies the centuries in the middle of the 5th millennium BC as the period of most intense activity.

The outstanding finds came from a complex sequences of deposits within and near a paleochannel of the river Eden, which made possible the preservation of organic materials like wood. They include 600 ochre fragments, as well as two wooden tridents and a trunk with beaver gnawing marks currently displayed at Tullie. A large wooden platform was also found that had been constructed in this channel in the earliest Neolithic period and was the focus for votive deposition and other activities.

The evidence suggest that the encampment was perhaps used mostly in the spring/summer months and that at this time, bands from the wider geographic region met at Stainton West, as well as other similar places by the river Eden and by the Solway Firth, to take advantage of the resources of the area.