This is the first of our regular boots-on-the-ground blog updates detailing the exploits of the archaeological dig currently being undertaken at Wintringham; the finds they find, the trenches they dig and the friends made along the way. I'm Harry, your friendly neighbourhood blogger, and I shall be guiding you through the dig step by step, as it happens, so you don't miss a thing. Hopefully you shall learn something of what it is to be an archaeologist, as well as the highs and lows of our quest for knowledge and old stuff.

This week saw the introduction of several new trainees to the site, fresh faced, orange-clad and bushy-tailed, eager to face whatever the weather could throw at them. They swiftly set to work on the densest area of archaeology, where there appears to be a centre of activity starting in the Roman period and possibly continuing for several centuries into Saxon times, lying at a crossroads between an earlier Iron Age trackway and a later droveway. This activity also includes numerous (possibly Roman?) enclosures surrounding the trackway, forming what may be a settlement, although it is too early to be sure. Much more hard work and exciting excavation stands in the way of that final interpretation!

Over the past few weeks, the team have been carefully unearthing the story of the Iron Age trackway leading to the 'settlement' from the east. We have been excavating the drainage ditches that would have run either side as it made its way westwards, widening into an enclosure as it neared the centre, possibly used to corral livestock such as cattle. This feature is called a Banjo Enclosure (due to its shape; the trackway forms the neck bit of the banjo, and the enclosure forms the round bit that you strum…I'm not a musician) and is commonly associated with the middle Iron Age of around 2500 years ago.

We have certainly come across some trials and tribulations in these ditches, most notably a particularly elusive natural geology. The natural clay (that is, the geology that existed on the site before human activity) is the archaeologist's guide to whether or not they have reached the base of their feature (their ditch, pit etc.). Once the soil above this 'natural' has been removed through excavation, you are looking at the feature close to how it would have looked when it was first created. In theory, fine. In practice, what appears to be natural may actually be a layer created by human activity (such as the soil that naturally accumulates in a feature after it is abandoned), with archaeological finds within. One minute you think you’ve found your lovely honey-coloured clay, the next a fragment of animal bone pops out of it, and so down you continue. To my mind this demonstrates the unpredictable nature of archaeology - exciting if baffling! Nevertheless, down we dug until we were certain we had reached the bottom of the original Iron Age ditch. Then we had the water table to contend with, beginning a King Canute style battle, armed only with buckets and the sheer stubbornness of an archaeologist who will get their photograph come hell or high water (table). Eventually, we won.

In the end, these trackway ditches have revealed an informative series of three distinct layers. These layers of earth are laid down (through natural deposition or human backfilling) one after the other. Therefore, the layers at the bottom are older than those on top. Imagine a wedding cake. You lay down a lovely layer of sponge, then some icing, then some more sponge and so on until gravity gets sick of your nonsense. The bottom sponge layer is oldest, the icing is a little younger, the sponge laid above this is younger still etc. Now replace delicious sponge and buttercream with soil and silt and you have the idea. Each layer usually represents a different phase in time, changing its colour and material due to varying local climatic conditions at the time of the layer's deposition, such as moisture content or level of organic material. In the ditch in question, the three layers were distinct at first sight due to their varying shades of grey, yet also distinguished by the archaeological material found within, such as fragments of ancient pottery.

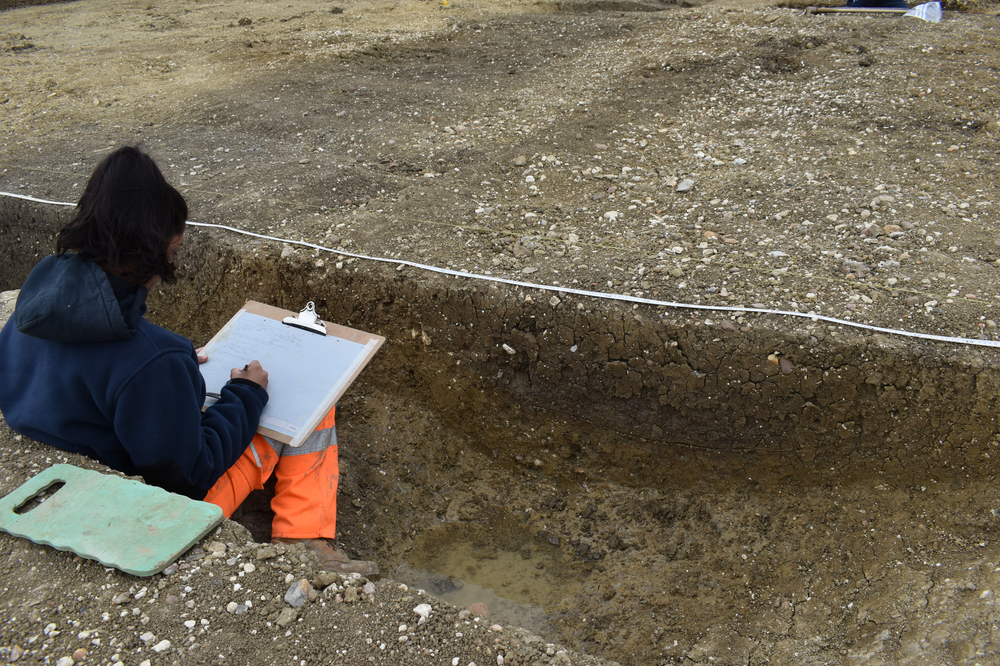

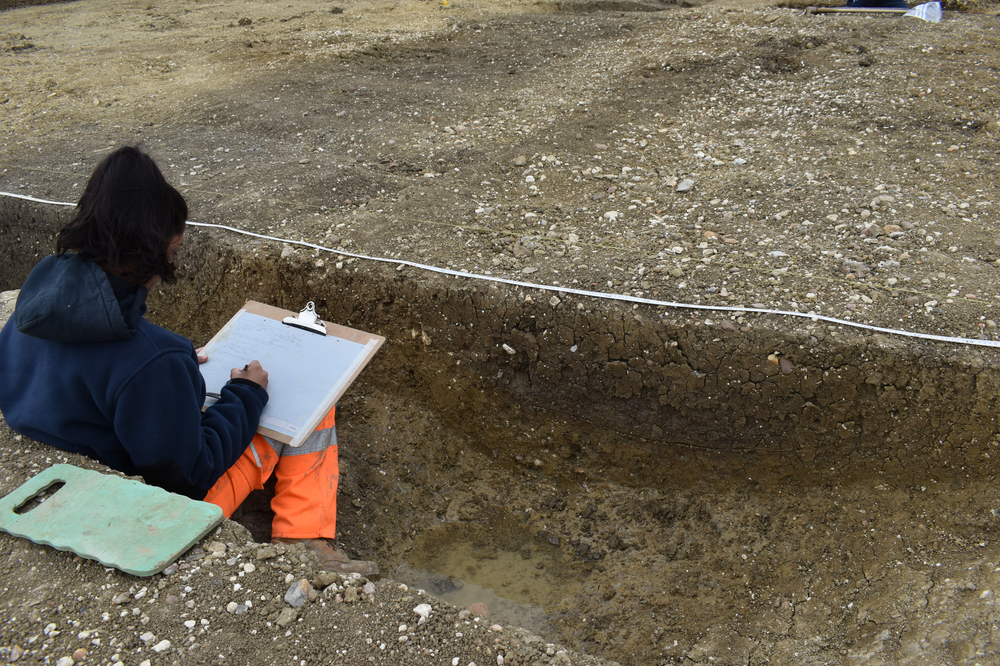

A cross-section of the Iron Age enclosure, showing the darker Roman re-digging of the ditch, diligently being drawn by Sarah.

Although we are waiting on the specialist analysis of these fragments, we know enough from initial examination of the style and material used that the pieces found in the lowest layer were in use during the Iron Age, around 2500-2000 years ago. Therefore, the lowest layer was likely gradually deposited around this time, meaning the ditch itself must be at least this old. Likewise, the next layer had what appeared to be later Romano-British pottery within it, suggesting this layer was deposited between 2000-1800 years ago. The thin layer at the top contained no pottery that could be found, but as a similar layer to the west contained Saxon pottery (around 1600-1400 years old), it seems likely that this layer is of a similar date. All of this reveals the vital role that pottery (and other finds that can be tied to a specific time period by their style and material) plays in dating archaeological features, and trying to untangle often complex chronologies.

Overall, it seems the trackway ditches were originally dug in the Iron Age, and at some point abandoned to silt up over time, with contemporary broken pottery occasionally being thrown in as rubbish. After many years, the ditch was recut to a more shallow depth and reused during the Romano-British period. The ditch finally fell out of use around the Saxon period; the thin upper layer appears to be a purposeful backfill to level the ground for some use other than livestock enclosure (as mentioned last post). This may have been anything from settlement to industry, although no firm evidence of this has been discovered…so far.

This upper layer continued to the west, into the enclosure and beyond the extent of the ditch, seemingly used to level natural depressions in the ground surface.

Although this is interesting in its own right, everybody unabashedly loves the impressive finds…which is exactly what Steve found on his second day deployed on site (no jealousy from this humble blogger, that's for sure). This took the form of a huge rim fragment of a Roman courseware jug, deposited towards the bottom of a ditch near the apparent centre of activity on site. Pottery fragments are informative or far more grounds than simply dating and phasing an archaeological feature. Once we know exactly where this pottery was made, we can start to understand in more detail the kind if people that lived on this site. What were they eating, drinking and storing? What kind of status were they? If we can find out where the pottery came from, what does this tell us about their influence in trade across Britain and even the rest of Europe and the world? Simple finds like this begin to paint a vivid picture of these lives lived over 2000 years ago, and I am sure we will have many more such finds emerge in the coming weeks.