July started by marking Tynwald Day, the national holiday of the Isle of Man, with the outstanding Mesolithic house found at Ronaldsway Airport. For Bastille Day, we travelled to northwest France, where OA worked at the Chauteau de Mayenne and discovered its intriguing story. We then started the Festival of Archaeology at Hinxton Hall, Cambridgeshire, where a volunteer on his first feature discovered an amazing ivory sword grip. Calling it beginner's luck is an understatement! And we concluded July and the Festival of Archaeology with a visit to Furness, in Cumbria, where our colleagues in Lancaster found the burial of an abbot with a stunning and well-preserved crozier.

Mesolithic Isle of Man

The first #OAat50 highlight for July is packed with exciting discoveries. In 2009, OA worked on the extension of Ronaldsway Airport on the Isle of Man and uncovered a Mesolithic house from the first phase of colonisation of the isle, a Neolithic structure and pits, a Bronze Age settlement, and Iron Age roundhouses and burials.

The Mesolithic house is of great significance. While other Mesolithic houses have been found in the British Isles, none were as well preserved as this one, allowing us to understand the layout and organization of the space. A 7m-diameter pit was discovered, likely containing a brush-wood floor, surrounded by postholes that may have supported a conical teepee-like structure. The house was destroyed by fire, preserving objects from its occupation, such as 20,000 struck lithics, coarse stone tools, and charred hazelnut shells. Radiocarbon dating places the house at over 10,000 years old, providing the earliest evidence of settlement on the island. Some argue that the house's inhabitants were pioneer colonizers, as the rising sea levels separated the island from the mainland during that time.

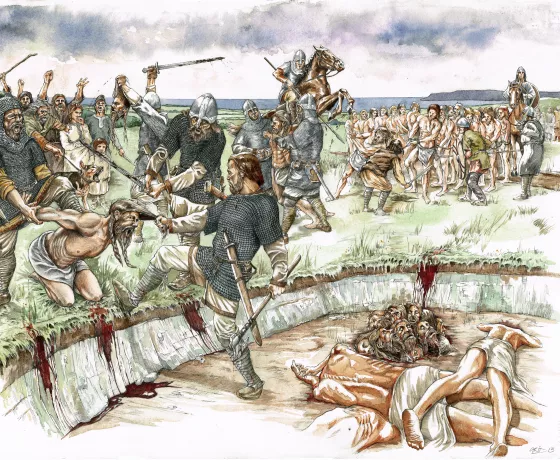

The Iron Age burials are also noteworthy, shedding light on how the Manx Iron Age people interacted with the past and their surroundings. Within one of the Bronze Age houses, the skeleton of a woman with a child on her chest was found, dating back to 800-400 BC, firmly in the Iron Age period. Another Bronze Age house contained the skeleton of a young man, dated between 50 BC and 100 AD, with numerous injuries to his limbs and torso, likely causing his death. These examples indicate that the Bronze Age settlement held special significance for the Manx Iron Age people, serving as a distinctive burial site and monument.

Revisiting the Chauteau de Mayenne

To celebrate the Fête National Française (or Bastille Day), we look back at an exceptional #OAat50 project in France, the excavations at the Chateau de Mayenne.

The excavations at the Chateau de Mayenne in the Pays de Loire in the 1990s was one of the first big overseas projects for OA. Like Oxford Castle, the conversion of a former prison in the chateau had revealed a rather surprising series of early features hidden behind the plaster. The main building, ostensibly a series of medieval vaulted chambers one above the other with an adjoining donjon, turned out to be almost entirely constructed of huge slabs of Roman granite brought from the nearby monument at Jublains, with arched windows constructed of Roman bricks.

The task for our team was to excavate the castle and carry out a complete building survey. This involved supporting 2 storeys of mediaeval stone vaults on a huge steel bridge, and digging out some 5 m of fill down to the base rock. We discovered that this basement had been filled with tons of early medieval occupation deposits like pottery, bone gaming counters and a considerable amount of environmental remains. External excavations uncovered remains of the mediaeval and post mediaeval phases of the castle.

The meticulous building investigation produced a complete measured and phased survey of the building showings its transition from chateau to prison, while excavation under the floor at the top of the donjon revealed traces of the oversailing timber upper storey like the one still extant in nearby Laval. Most startling was the fact that from the bottom of the basement to the top of the tower the mortar contained sizable pieces of charcoal which could be dated and showed that the whole castle had been built in the 10th century - though quite why a great hall with large windows and an adjoining tower had been built on the rock outcrop above the River Mayenne remains something of a mystery.

The Chateau is today a magnificent and well-visited museum and OA is proud to have participated in such a successful project.

A once-in-a-lifetime find

To kick off the Festival of Archaeology with our #OAat50 highlight, here is a beautiful memory told by Paul Spoerry, our recently-retired Cambridge office's regional manager, about a special Saxon sword from Hinxton, Cambridgeshire.

Read Paul's story about this special find (and why you should try your hand at archaeology!) in full

"In 1994, OA's Cambridge office was excavating at Hinxton Hall ahead of construction of the new research facility that would lead Europe’s part in the race to crack the human genetic code. Evaluation had revealed a well-preserved early medieval settlement, which lasted from 6th to 13th centuries.

I was directing a team of 25 archaeologists and a handful of volunteers, I instructed a volunteer, the enthusiastic but inexperienced boyfriend of one of our staff, to dig an apparently unremarkable pit, the first proper feature he had ever tackled. In time-honoured fashion for volunteers on their 1st dig, the pit quickly started generating late Saxon finds. After 1 hour he was waving a bone object at me, the like of which I had never seen before. We marvelled at it, decided it was some kind of handle, went through the small finds procedures and carried on. I was not alone in not knowing what it was, even if it did seem potentially significant.

Later, our finds specialist, Ian Riddler, identified this as a walrus ivory sword grip, probably dating with known Scandinavian objects of the 9th century. Ian also confirmed that it was “the first example of a sword grip made from this material to have been found in this country”. Hooray we thought, but the story did not end there.

The following year Monty, our ex-detectorist, handyman, photographer and subsequently professional archaeologist, found a probable iron sword pommel in one of the boxes of ferrous finds from spoil heaps, that he had periodically detected during our excavations. It came from the spoil from a section adjacent to the sword grip pit. The archaeometallurgist Brian Gilmour confirmed that this was ‘the pommel of a sword of Pedersen type L’, a native Anglo-Saxon type dating to the mid-9th to later 10th century."

The lesson from this story is, as a beginner, you will always get the best finds on your first dig!

The crozier from Furness Abbey

In 2010 we discovered this spectacular crozier during excavations at Furness Abbey. It is made of copper-alloy covered with a fine coat of gold; the main part of the crook is thought to date to the 12th century, but the cruder panels representing St Michael battling the devil may have been added later.

There are so many outstanding things to this find: the crook preserved some pieces of the original staff in the socket; made from ash wood, it preserved traces of yellow coloured paint on most of the surface, with a thin band of white paint around the mouth of the croziers socket, with fine white lines ending in a white dot, running out at 90 degrees from it. Inside the socket were the remains of textiles; a creamy coloured linen, and an uneven, possibly patterned, coloured fabric; probably silk, the last remains of the ‘sudarium’ which is a ribbon or cloth attached to the crozier at the base.

The crozier was found in the crook of a skeletons arm, with an iron ferrule from the other end of the staff, down by its feet. The body was that of a 5’7” tall man, 40-50 years old, and of local origin. He was very well-built, and ate a diet very rich in protein, and suffered from a spinal condition called DISH, associated with obesity and Type II mature-onset diabetes. He was also buried with a finger ring of gilded silver with a rock crystal cabochon on his right hand, dating to the mid-12th to mid-13th century.

The man was likely an Abbot, although unusually he was buried in the presbystery, which is usually reserved for wealthy patrons, rather than the chapter house which was the seat of the Abbot's authority. Though he may well also have been a member of a local wealthy patronal family or other figure of significance. He was buried in a nailed wooden coffin around cal AD 1360-1390, showing that the ring and crosier was of some age when buried with him, and thus likely being retired with him.

The excavations too place ahead of works to underpin and secure the foundations of the standing remains of the Abbey for English Heritage.