Our #OAat50 August highlights took us first to Fleet Marston where excavations of a Roman settlement for HS2 led to the discovery of a Roman cemtery and some rather different burials. We then revisited an Anglo-Saxon cemetery in Cambridgeshire with some very special grave goods. From there we jumped all the way back to the Palaeolithic to explore what Britain looked like then. Then excavations at the church of St Michael's in Workington, Cumbria, revealed an exciting potential murder mystery set in the Middle Ages. We ended the month in France, where we looked at the work OA did at the Chateau de Falaise, birthplace of William the Conqueror.

Headless Romans at Fleet Marston

For this week's #OAat50 highlight, we visit a fascinating site in Buckinghamshire. In 2021, archaeologists from Oxford Archaeology and Cotswold Archaeology, working as COPA Joint Venture, uncovered parts of a Roman town at Fleet Marston, outside Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire. The work was carried out for Fusion Joint Venture HS2 Enabling Works Contractor as part of the HS2 programme. Until the HS2 work, little was known about this large roadside settlement.

In the mid-1st century AD, a few years after the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43, a major Roman road, today called Akeman Street, was laid out. This connected the Roman towns of Verulamium (St Albans) in Hertfordshire and Cirencester in Gloucestershire, and part of it ran through Fleet Marston, where the Roman settlement subsequently developed.

The excavation exposed a section of road surface, as well as rows of conjoined plots that were established either side of the road. These plots date to the mid-2nd century onwards and show how the settlement expanded beyond its core area (which remained unexcavated). The activity within these plots was of a mixed nature. Large amounts of pottery, animal bone, and objects such as spoons, dice, and gaming counters, suggest domestic and leisure activity, but coins, metalled surfaces, metalworking waste and ovens point to activities of a more industrial or commercial character. These activities catered for travellers as much as inhabitants.

A second well-made Roman road was encountered in another area of excavation. This is provisionally identified as the road connecting the settlement with the Roman town at Dorchester‐on-Thames. Settlement features here were sparse, suggesting that this part of the site was largely confined to farming. A corndryer built after the late 3rd century AD was used to process grain for storage or market. Such structures were also associated with malting and brewing.

One of the outstanding discoveries was a late Roman cemetery of over 400 burials. The size of the cemetery suggests that there was a population influx in the later Roman period, linked perhaps to increased agricultural production. Preliminary examination of the skeletons has revealed that some individuals had had a hard life, consistent with heavy toil in the fields. As is typical of late Roman cemeteries, grave goods were few, but where present included pottery drinking vessels, coins, and beads. Nails attest to the use of coffins and occasionally stones were used as pillows. Several decapitated individuals, the head being placed between the legs or next to the feet, were recorded. While it is possible that these represent criminals or other outcasts, decapitation appears to have been a normal, albeit marginal, burial rite during the late Roman period. Similar burials were found at another OA site, this time in Wintringham, Cambridgeshire, which featured on Digging for Britain earlier in the year.

An Anglo-Saxon cemetery near Cambridge Airport

If you're into Early Medieval archaeology, this week's #OAat50 highlight is a real treat.

In 2007 our Cambridge Office (then the Archaeological Field Unit) evaluated a site at Hatherdene Close next to Cambridge Airport. Roman and Middle Saxon remains were known from nearby, but ten Anglo-Saxon burials were found. We would have to wait 9 years to excavate them fully...

When we eventually excavated in 2016, we found an extensive cemetery of 126 individuals with spectacular grave goods: jewellery such as copper-alloy brooches, beads of amber, glass and crystal, as well as pottery vessels and iron weaponrydating between 440 to 650 AD. These finds give us a glimpse of dress in the past.

The spectacular brooch’s design is ambiguous: beaked quadruped, or a feline eating another? It was repaired and modified with iron rivets punched into the animal’s rear, before eventually being buried with its owner.

Weapon burials are not uncommon for the period but here their positioning was unusually consistent: spears normally by the left shoulder and always accompanied by a belt buckle and knife at the waist. This may have been a common tradition specific to this community.

Brooches may also have formed links across the generations. 25 individuals wore matching pairs of brooches that can be dated to a slightly earlier period. Interestingly, the mismatched pairs of brooches were later: perhaps they were split up, lost or broken and handed down between generations?

The cemetery had many multiple burials, both one after the other or together (sometimes damaging the first) with up to 3 individuals at once and combinations of the two. Some graves were even re-opened to disturb them or potentially rob them.

The earlier graves were laid out on a different alignment compared to later ones. One was radiocarbon dated to 343-535 AD, so at the end of the Roman period. This is intriguing, as the whole cemetery 5th-7th century graves lay between a timber structure and the remains of a Roman cemetery.

Anglo-Saxon cemeteries often re-used earlier monuments, but it is rare to see such close links in time between a Roman cemetery and people of Anglo-Saxon culture using the same site.

Lost Landscapes of Palaeolithic Britain

This week's #OAat50 highlight is an OA publication that revolutionised our understanding of the Palaeolithic in Britain. "Lost Landscapes of Palaeolithic Britain" was a collaboration between OA and a team of leading academics aimed at disseminating to a wider audience the results of projects supported by £8.8 million funding from the Government's Aggregates Levy Sustainability Fund (ALSF) administered by Historic England.

The ALSF projects have completely transformed our understanding of the Palaeolithic. This is a period of multiple Ice Ages interspersed with warmer periods, which forms the backdrop for human evolution. The benefits to archaeology and for the interpretation of these fragile remains from this ancient epoch have been incalculable. The academic team was led by Professor Mark White of Durham University. Outputs from the project included an update of The English Rivers Palaeolithic Survey (TERPS) artefact database and a report to inform future research activities undertaken as part of the National Heritage Protection Plan.

A key and concluding part of the project was the production of a peer-reviewed monograph, specifically designed to provide an engaging and accessible commentary for the non-specialist, reaching out to curators, planning archaeologists and those working in industry and commercial units. The aim from the outset has been to bridge the gap between achievement and awareness of the huge contribution of the ALSF to this remote and often enigmatic period.

The official book launch of Lost Landscapes of Palaeolithic Britain was held at an evening reception hosted by the Society of Antiquaries of London in the beautiful rooms at Burlington House, Piccadilly. In 2018 Lost Landscapes won the Current Archaeology Magazine’s prestigious Book of the Year award presented by Julian Richards. Voted for by subscribers and members of the public, the awards recognise the outstanding contributions to our understanding of the past made by people, projects, and publications featured in the pages of CA.

A medieval murder mystery?

This week's #OAat50 highlight takes us to Workington, Cumbria, and a potential early medieval murder mystery.

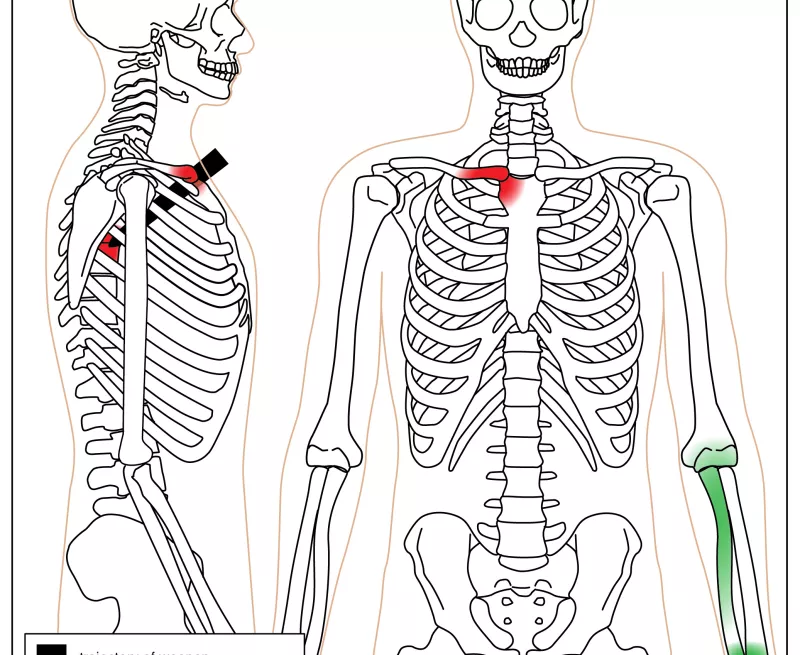

This intriguing drawing indicates some of the final injuries suffered by an individual buried at Workington in the 11th century looking out over the Irish Sea; but what are these injuries, and how did the person get them? The story begins in 2014 when we were commissioned to conduct the analysis and publication of some archaeological work conducted on St Michael’s Church in the late 1990s. This included a detailed investigation by our burials team of skeletal remains dating to the early medieval and medieval periods.

One interesting burial contained two individuals within a stone-lined grave, the top burial having suffered some unusual injuries. The individual was 25-35 years old, grew up locally, and was estimated to be a male. They had suffered fractures to their left forearm, elbow, and wrist, which were healed, but at some point had become infected. Shortly after this something major happened as the individual died and was buried. Multiple blade injuries in the upper chest (peri-mortem sharp force traumas) seem to give a clue about the method of death; or did they?

At least 4 blows of a sharp bladed implement had been stabbed into the area of the clavicle (collar bone) and manubrium (top of the breast bone) penetrating through the chest to the 3rd and 4th thoracic vertebrae. These injuries were closely spaced, which suggests the individual was killed with several short stabbing blows. This, combined with the lack of defensive injuries may indicate that this happened when the person was immobilised or unconcious.

Another possibility is that very shortly after death, the heart was removed from the chest, in a post-mortem ablation. This was a common funerary practice amongst higher status individuals in northern Europe, so perhaps this individual was the first of a new European trend of burials.

Whichever it is, this burial was a fascinating insight into individuals lives and deaths in early medieval Cumbria!

Chateau de Falaise and William the Conqueror

For this week's #OAat50 highlight we go back to France and to another castle project. After the success of OA’s work at the Chateau de Mayenne, OA had the privilege to carry out another complex castle excavation in Normandy at the Chateau de Falaise.

The Chateau de Falaise is a formidable fortification sitting on a rocky outcrop (the translation of Falaise is ‘cliff’) and is steeped in the history of both England and France. It is the birthplace of William the Conqueror and remained in the hands of the Anglo-Norman kings until 1205 when it was conquered by Philippe Augustus, the first to call himself "King of France". Even so, its original form was little known, so the excavations were a great opportunity to better understand the phases of this extraordinary site.

In 2008 the OA team started the excavations of the Northeast Bastion of the Chateau. The structure was a projecting triangular defence built in the early 13th Century. Falaise was captured by the English during the Hundred Years’ War, and it was possibly during this period in the 15th century that the bastion was infilled, most likely to buttress the walls against cannon attacks and convert the structure to an artillery platform. The 3-month-long works excavated the 5-metre deep bastion in its original form, and revealed the circular tower complete with many graffiti carved by soldiers during the Hundred Years' War.

The chateau now hosts the Château Guillaume-le-Conquérant museum that beautifully illustrates its history.