It’s not every day you find a Roman kiln. It’s certainly not every day you find one as intact, and with so many artefacts still in place, as the one recently discovered at Wintringham.

Finding the kiln

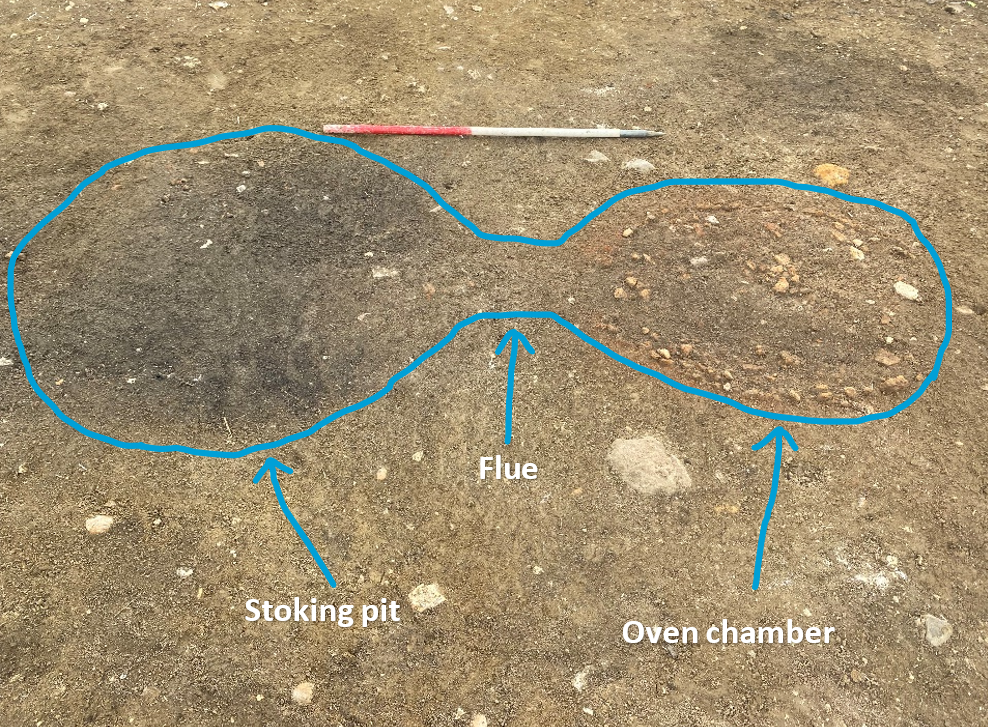

Archaeologists often don’t know what archaeological features are there until we start excavating. Sometimes however, we can spot recognisable patterns or identifiable features in the ground that provide helpful clues as to what the area might have been used for. Geophysical surveys (using different diagnostic equipment such as magnetometers) can also help to highlight distinguishable features where the soil is particularly disturbed. Ditches are recognisable in that they typically show up as long, linear or curvilinear lines. We can often identify inhumation graves (graves with human remains buried intact) from their oblong shape. Kilns can be recognised by their most common ‘keyhole' shape (circle with a skirt) or a ‘dumbbell’ shape (two adjoining pits), and usually contain a dark soil surrounded by an orange crust. It was this dumbbell pattern with a ring of orange fired clay fragments recently found on the edge of the settlement that got the team excited.

Dumbbell shape of the kiln pre-excavation, as seen in the ground.

The excavation process

The stoke pit and flue after one half had been excavated.

We decided to only excavate half of the kiln to begin with, cutting a half section lengthways down the ‘axis’ of the feature. This allows us to see the formation of the different materials which filled the feature, and from this, we were able to see the initial excavation of the ‘hole’ to build the kiln, the construction of the kiln chamber, the different soil fills that developed over time during its use and its disuse, and the artefacts found in the fills. All of these will be analysed in the post-excavation process to learn more about how the kiln was created, used and what happened to the structure after it was no longer in use. For example, the above picture shows a half section of the stoke pit and flue. The dark blackish material with red fired clay at the base of the stoke flue and pit (shown in the photo above) could possibly be a layer of undisturbed rake-out from the oven’s final firing before it was abandoned, or even parts of the flue arch.

The half-sectioned oven chamber with fragments of pottery and kiln furniture at the bottom.

The oven chamber was excavated last as it was the most fragile part of the feature. As you can see from the above photo, it revealed a central ‘tongue support’ – that’s the central plinth coming out in the centre of the kiln - used as an internal ledge to support the kiln bars and furniture, such as kiln plates, on which the pots were placed onto. The oven chamber and tongue have been lined with a layer of clay which provides insulation and support for the kiln load. The bits of fired clay you can see ‘floating’ within the fills are likely to be part of the lining and structural fragments from above the ground that didn’t survive.

Within the oven we found numerous fragments of pottery. Some theories suggest that pottery found within abandoned kilns are the expendable pieces that are at the bottom of the load or maybe not as well fired (Swan, 1984). This could be the case with our kiln because of the presence of ‘waster’ fragments found; a term for fragments of pottery that are damaged or misshapen during the firing process. A number of 'kiln bars' and larger fragments of the oven’s clay superstructure were also found. Kiln bars would have been used to span the space between the tongue and the wall, like spokes on a wheel. They acted as plinths in the oven from which pots were placed on so that they could be stacked on top of the furnace underneath.

A possible fragment of an internal ledge formed into the pit lining, giving the end of the kiln bars something to rest on.

Assistant Supervisor Archaeologist Sam carefully drawing the kiln's section.

After one half of the kiln had been fully exposed and recorded, the other half was excavated to see the full extent of the kiln. This revealed an almost complete (albeit broken) pot, along with more waster fragments, kiln bars and kiln plates.

The kiln when fully excavated.

Identifying the kiln

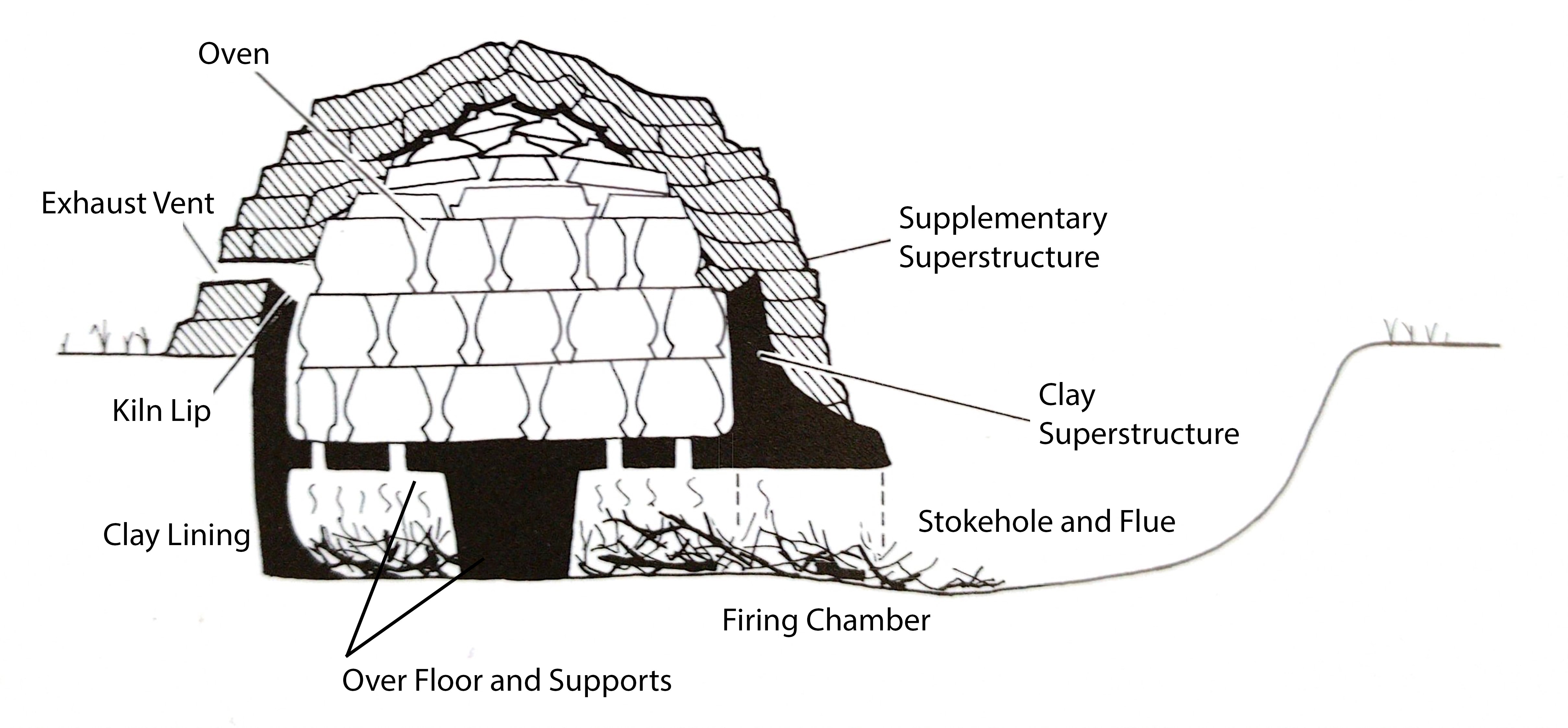

From the shape and the constriction of the kiln found at Wintringham, we can identify it as a beautiful, classic example of a sunken Romano-British updraft kiln.

Image edited from: V. Swan (1984) The Pottery Kilns of Roman Britain.

At one end of this single-chambered, single-flued kiln is the ‘oven chamber’; this is the oven where the pots are fired, made from a superstructure of fired clay. We don’t really know for sure what the kilns would have looked like above the ground. They were probably temporary structures that were destroyed after each firing to reach the pots, although we rarely find anything when excavating to suggest how the top would have looked.

These kilns were typically used seasonally, and often found on rural sites. The furniture such as the kiln bars and plates were portable, meaning they could be taken by the potter from site to site, and so often the only evidence we find are the broken pieces left behind (Gibson and Lucas, 2002, p.103). Below is an example of one of the numerous fragments of kiln plates found. They are made by flattening a layer of clay between handfuls of chaff, typically to the size of a dinner plate. The chaff provides structure to the plate and also probably helps the plates to dry without sticking to each other when being made.

Fragment of kiln plate showing imprints of chaff reeds used to reinforce the plate and prevent sticking. These were probably mass made for firings.

The oven chamber is connected via a narrow flue to the 'stoking pit'; another typically roundish hole where the ashes are raked out into after each firing to make space for the next load. These usually point into the prevailing wind, allowing the potters to take advantage of the up draught. As you can see from the photos, this filled up the stoking pit with a dark blackish brown ashy material.

Further analysis of the structure, its finds and the soil samples in the coming months will tell us more about what this kiln was used for. What type of pottery was being made in this kiln? Was it reused over a long period of time or does the pottery found point towards it being a temporary structure? Are there similar kiln structures found locally that can help us to narrow down a date?

Bibliography and Further Reading

Swan, V. (1984), The Pottery Kilns of Roman Britain (with 5 micro-fiches), RCHME Supplementary Series 5, HMSO 1984.

Other posts in this collection

Read our latest posts about the archaeological investigations at Wintringham.