Through October's highlights we travelled from the Neolithic, with the Yarnton hall, all the way to a post-medieval burial ground in Kingston upon Hull. A large settlement uncovered at Burwell, Cambridgeshire, gave us new insights into life in the Late Bronze Age. And we also celebrated 30 years of working with the Royal Household and Historic Royal Palaces by reminiscing about the first excavations OA carried out at the iconic Tower of London.

Exploring the Late Bronze Age at Burwell

The first #OAat50 highlight for October is an exceptional Late Bronze Age settlement site in Cambridgeshire.

In 2021, OA excavated an 8ha site in Burwell in south-east Cambridgeshire. Located on a chalk escarpment close to the fen-edge, the team uncovered exceptional remains of a Late Bronze Age settlement, dating between 1150 – 800 BC.

Open settlements comprising post-built roundhouses, raised storage structures and pits of varying sizes are common in the Late Bronze Age but on individual sites the scale of these settlements can be very modest. By comparison, Burwell is on a different magnitude, both in terms of the density of features and material culture: OA uncovered many roundhouses, granaries, and hundreds of pits, including 30-40 large ones structured like storage ‘silos’ with considerable amounts of objects that had been deposited in them.

Rich, midden-like assemblages of locally made flint-tempered pottery (130kg) and animal bone (201kg) were found in the backfills of the largest storage pits. In the base of one such pit a double horse burial was uncovered, placed with great care despite the 2.3m depth of the pit. The very deliberate act of burying two highly-prized animals in this way must have been symbolic, and the same may be true of disarticulated human bones – particularly fragments of skull and femora (upper leg bones) – found in some of the pits.

Craft activity was evident from the recovery of bronze pins, spindlewhorls and worked bone tools. In addition, one of the largest assemblages of Late Bronze Age metalworking mould fragments recovered in the east of England – from a single small pit – indicates on-site production of socketed axes, swords/blades, strap ends, bronze plate and micro-pins or rivets. The most unusual piece is a highly ornamented plug from a socketed axe core, which has a zoomorphic design consisting of an animal’s head.

A rare Neolithic hall at Yarnton

This #OAat50 highlight takes us to Neolithic Oxfordshire, to a site that revealed one of the few known buildings from the period when farming was first adopted by communities in Britain.

The hall, one of Britain’s earliest buildings, was discovered by Oxford Archaeology in 1996 in a gravel quarry at Yarnton.

Erected in c 3800 cal BC by some of England’s first farmers, this enormous timber-framed structure, 20 metres long by 10 metres wide, would have had daub walls and a thatched roof.

They chose a woodland clearing on an island in the floodplain of the Thames, around 500 metres from the river and the building’s impact on the hunter-gatherers who had previously occupied the area must have been dramatic.

A foundation deposit of cremated human and animal bone (pig) was placed around one of the very large posts, and smaller quantities of human and animal bone came from other postholes. The condition of the bone sadly made it impossible to identify the age or gender of the individuals. Were they ancestors of these new inhabitants of the valley?

We do not know how the building was used, as it seems to have been kept clean; rubbish was probably taken to the nearby midden that we excavated in the next field. Multiple small postholes within the west side of the building suggests that it had an upper storey or loft, and it could have had a central partition.

The structure probably served multiple purposes: as a home for the first immigrants and then as a communal hall for the group as it expanded and started to farm adjacent areas. Its construction was very similar to the halls that these farmers built in their continental homelands and it would have created a sense of familiarity and permanence.

Excavating a post-medieval burial ground...during a pandemic

This #OAat50 highlight is the work OA undertook at Kingston upon Hull, as part of the improvement of the A63 Castle Street on behalf of National Highways and Balfour Beatty. A truly outstanding project because of its scale, the innovative approach required, and the thousands of personal stories we uncovered.

OA was involved in the project from the very beginning in 2013 and, through the different phases, we explored through different methods parts of the medieval town defences, the Georgian Humber Docks, the remains of the Georgian gaol, and various pre-cemetery features, including the first archaeological evidence for Hull’s little-known twelfth-century predecessor. In 2020-21, the excavations focused on the Trinity Burial Ground, which was the most complex and sensitive part of the project. And all this at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, which required major adjustments to our fieldwork.

Hundreds of monuments were recorded and carefully moved to storage. A tent was built over the 3000m2 area to ensure that the excavation of the largest assemblage of funerary remains from northern England, comprising thousands of skeletons, coffins, and artefacts from earth graves and brick tombs, could be undertaken privately. A bespoke compound was established, where the funerary remains could be washed, dried, x-rayed, stored, and recorded for analysis by our specialists, before being reburied on site, as requested by the Church. This complex process was aided by our self-designed digital system that efficiently integrated on-site recording and the tracking of funerary remains through processing, permitting them to be reunited to ensure that individual skeletons were reburied with their personal effects.

By the end of the excavations, the team had recovered, assessed, and reburied the remains of at least 8791 individuals, 1500 of whom were analysed in the on-site laboratory, with a proportion sampled for ancient DNA and isotopes.

Since the end of the excavations, we have been analysing the findings to understand the lives of Hull's residents between 1785 and 1861. The stories we uncovered include possible female boxers, evidence of surgical amputation, evidence of body snatching and anatomisation, and the remains of probable victims of a shipping disaster. You can read more about the people and their personal possessions here

https://nationalhighways.co.uk/.../a63-castle-street.../

Colleagues and experts at Archaeology at Durham University and The Francis Crick Institute continue to carry out new research on the evidence from Trinity Burial Ground, always uncovering exciting new details about the past of Kingston upon Hull.

Rediscovering the Tower of London

Over the decades, OA has had the immense privilege to work on some unique and iconic locations that include some Historic Royal Palaces.

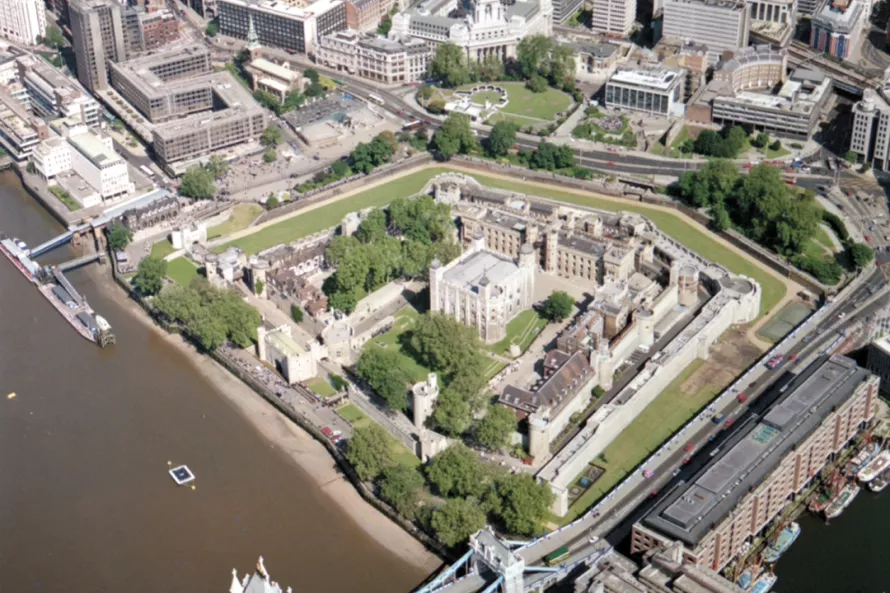

This #OAat50 highlight is about one of these locations that is famous all over the world and has become synonymous with London and the UK: the Tower of London. This was a real "pinch-me" project for the archaeologists involved.

The Tower of London was among the first castles built on the orders of William the Conqueror after he defeated the Anglo-Saxon king Harold Godwinson at Hastings in 1066. In its very long history, the Tower underwent several modifications and expansion to suit changing uses. In much more recent times, works were undertaken at different times to update the Tower, its services, and infrastructure, as well as for restoration purposes.

In the early 1990s OA entered into a framework agreement with the Royal household and Historic Royal Palaces to supply heritage services. Early archaeology works under the agreement included monitoring of trenches for a new ring main in the Tower of London which revealed the line of the City’s Roman wall below one of the curtain wall towers.

Even more exciting was an investigation into the Tower moat. The moat had been infilled in the mid-19th century and the possibility of re-establishing it was under consideration. The trenching works provided fabulous results; mapping the foundations of the North Bastion (a forward defence, destroyed by bombing in the second world war) clarifying that the moat had partially been filled with the demolition of the Grand Storehouse (the accidental burning down of the Grand Storehouse may have contributed to the decision to infill the moat with handy demolition material).

Most impressively, thanks to this work, we were able to discover a previously unknown, partially built and collapsed former bridge that led to the Tower's entrance from the west, significantly adding to the understanding and history of this amazing World Heritage Site.

To this day, OA continues to carry out exciting work at the Tower, Historic Palaces and Royal Households.