To kick off OA's 50th birthday, we started with the finds that symbolise OA's three regional offices. We then went back to 1973 Oxford to explore one of the first sites excavated by what was then the Oxfordshire Archaeological Unit; looked at a runic curse tablet from Ipswich; travelled to West Yorkshire to find an exceptional Iron Age chariot burial.

All Saints church excavations, Oxford, 1974-74

In 1973, the newly established Oxfordshire Archaeological Unit started works at the All Saints church on Oxford's High Street. The excavations were carried out ahead of work to convert the church into Lincoln College Library, as it is known today.

The conversion work included an underground reading room which would impact any potential archaeology from the church's long history. The Classical building that is still visible today was built in the early 18th century, but the church was first mentioned in 1122, so the Unit was called in to explore and record any archaeology on site.

Once the Unit's archaeologists, led by OA's first director, Mr Tom Hassall, got through the 1.5 metres of rubble that had been put in place to create the foundations of the Classical building, they uncovered four phases of the medieval church and several phases of domestic use dating to the Anglo-Saxon period. The oldest surface was dated to between the end of the 9th century and mid tenth century (880 to 950 AD), or the early days of the Anglo-Saxon burh of Oxford. In the Norman period, the first All Saints church was built in stone on the site previously used for domestic activities; in what would have been the yard of the early church a few graves were also found. The Unit's archaeologists were able to map the expansion of this church through different phases until its collapse, documented to have occurred in 1699.

You can find the excavations report in Oxoniensia volume 39 (1975).

Early medieval curses from Ipswich

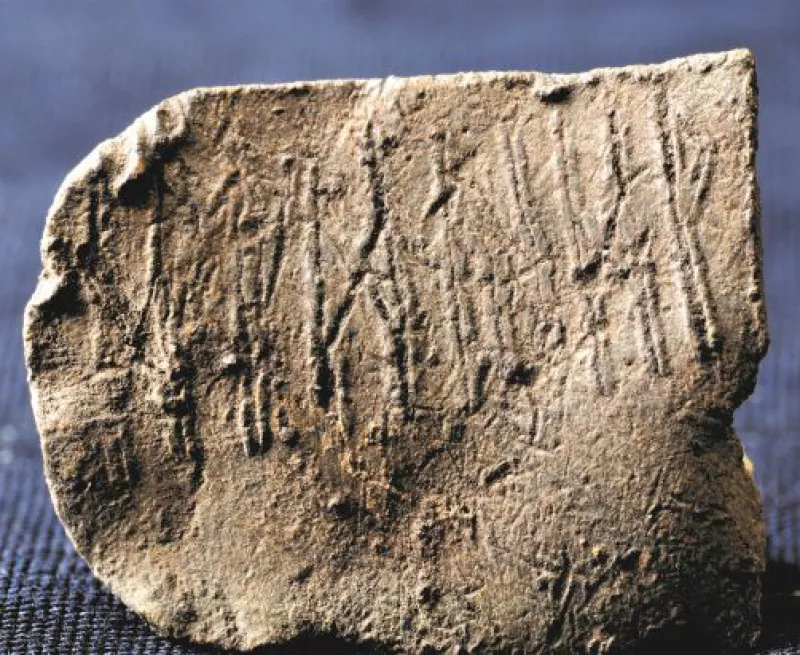

In the course of excavations at Lower Brook Street in Ipswich, OA archaeologists found this lead plaque, approximately 2 x 1.5 cm in size, with runes on one side, which dates to between the 8th and 11th centuries AD.

The transcription of the runes into Old English reads d͜eadisdw[ which can be translated as "Dead is dw". Thanks to other similar finds from Norfolk and Cambridgeshire, the specialists consulted by OA (Dr Martin Findell and PhD researcher Jasmine Higgs from University of Nottingham) and were able to complete the inscription as deadisdwe/erg or "The dwarf is dead".

Old English medical texts provide some helpful context for this puzzling inscription: dwerg or dweorh is used to indicate a serious illness with symptoms like seizures and paralysis. One text, known as the Lacnunga, attributes this illness to a malicious dwarf who claims the person affected as his servant and binds them with a harness. The cure comes about when the dwarf's sister or some other supernatural being intervenes to free the patient.

The other known fragments similar to the one from Lower Brook Street were pierced, indicating that they were affixed to some object or surface. It is then likely that this plaque was a charm whose inscription protected people from this terrible illness or was a form of prayer asking for healing for those already affected.

A real surprise: the Ferry Fryston chariot burial

The rare chariot burial (the Ferry Fryston chariot), found near Ferrybridge in West Yorkshire during the upgrading of the A1 in 2003, was part of a funerary landscape created over several thousand years, from the early Bronze Age to the Roman period, including cremations within ring ditches, a beaker burial, also containing a dagger, and an archer’s wristguard in Langdale tuff, a possible timber structure and a pit alignment. It was found some 30m from a square timber enclosure, of a type often interpreted as a shrine.

The two-wheeled chariot had been placed in the grave intact, in an upright position, though without the horses that would once have pulled it. This is similar to a few other chariot burials (the Pexton Moor-type), mostly, like this one, outliers to the main concentration of chariots, in the Wolds. Its wheels did not match precisely, indicating that the vehicle had been cobbled together, presumably for the burial, as it would not have functioned well over a long distance. The body of a man, aged 30-40 years, had been laid on his back, with his bent legs over the axle and his head towards the north, over the pole. There were few accompanying grave goods, only a single brooch, suggesting that he had been buried clothed, and parts of a pig, perhaps the remains of a funerary meal. The burial took place in the Iron Age, probably in the fourth to second centuries BCE.

A mound had been raised over the grave, the material being upcast from a surrounding ditch. The remains of at least 25 cattle were found in the bottom of the ditch, presumably having eroded from the top of the mound. Perhaps the most unusual aspect was that its upper fill contained nearly 13,000 cattle bones, from a minimum of 162 animals. Radiocarbon dating indicates that these were deposited in the first to third centuries CE, some 500 years after the chariot had been buried. Even more surprisingly, stable isotope analysis suggested none had been reared locally, instead coming from a wide swathe of northern Britain, and perhaps as far away as what is now Scotland.

Other posts in this collection

Read the latest posts celebrating our 50th year in archaeology.