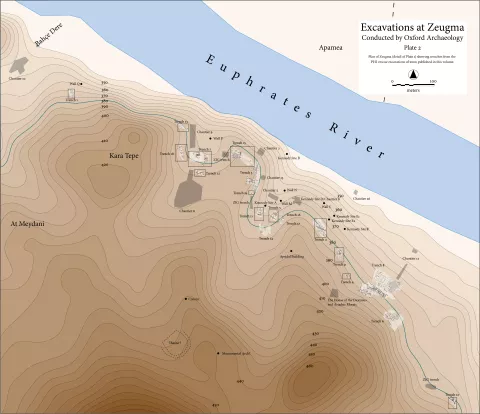

In 2000, Oxford Archaeology was approached by the Packhard Humanities Institute to participate in an archaeological mission to excavate and record the ancient Roman city of Zeugma, on the banks of the Euphrates in Turkey. At the time, the site of the Roman city was about to be submerged by the water of the Birecik dam and within a few weeks, OA had mobilised a hundred archaeologists.

The reservoir was already slowly filling when Zeugma came to the attention of Mr David W. Packard. With the cooperation of Oxford Archaeology, who managed the excavations, and the Centro di Conservazione Archeologica (CCA) in Italy, who were in charge of the conservation, and under the auspices of the Turkish Ministry of Culture, the Packard Humanities Institute quickly organised work at the site to excavate and salvage parts of the city.

The excavations at Zeugma are undoubtedly one of Oxford Archaeology's highlights; they brought together an international team of archaeologists and conservation specialist and its amazing legacy can be seen in the outstanding mosaics that are now on display at the Zeugma Mosaics Museum in Gaziantep.

Zeugma's highlights

A Roman frontier city

Zeugma is the name given to the site of two towns located on opposing banks of the Euphrates. The fertile valley of the Euphrates river has been occupied since prehistoric times; in antiquity, it provided a natural boundary between the Eastern and Western worlds. It is said that Alexander the Great with his army crossed over the great river at this strategic point. One of his successors Seleucus I Nicator (312-281 BC), founded twin towns on opposing banks of the Euphrates, naming them Seleucia and Apamea after himself and his wife. Zeugma is the name later given to the site which includes both towns.

In the first century AD, the towns passed under Roman rule and a legionary garrison, the Legio IIII Scythica, was established here to protect what was the only permanent bridge across the Euphrates for several hundred kilometres. For 200 years the towns constituted an important trade link between the Roman and Parthian empires. By AD 200, when the city was at its peak, it had great military importance and vibrant commercial life which made it one of the great cosmopolitan centres of the Roman Empire. The city may have had a population of 50,000 - 75,000. On the west bank, the city extended over approximately 2000 hectares (4942 acres ) where high-ranking Roman officials, army officers and wealthy merchants built great courtyard houses containing fine works of art.

The good life in Zeugma came to an abrupt end with the Sassanid invasion in AD 252 when the city was sacked and burnt. Subsequently, a natural disaster might have almost completely buried it under tons of hill wash. However documentary sources tell us that there was a bishopric at Zeugma for several centuries. The last mention of Zeugma in written sources dates to 1048, just before the arrival of the crusaders. The actual location of the site was confirmed in the 1970s by the German archaeologist Jorg Wagner, although looters had unfortunately known about the site for at least two centuries. Many unique wall paintings and mosaics have sadly disappeared.

Since 1985, research excavation took place, furthering our knowledge of the international significance of the site. It was principally led by David Kennedy from the University of Western Australia, Catherine Abadie-Reynal, Professor at the University of La Rochelle, and Gaziantep Museum. Rescue operations began in earnest in 1996, followed by intensified efforts in 2000 supported by the Packhard Humanities Institute.

The luxurious courtyard houses

At Zeugma several courtyard houses were discovered, dating to the Roman period; they were richly decorated houses that most likely belonged to the richest members of society. The courtyard house -as its name suggests- is centred on a courtyard. This courtyard is open to the elements and is surrounded by colonnades on all four sides. The columns making up the colonnades sit on a plinth and support a roof over the passageway surrounding the courtyard. The rooms of the house opened off this walkway. The courtyards houses exposed at Zeugma had mosaic floors and, below, ground cisterns located to the side of the courtyard storing water. Usually the entrance from the main door of the house would lead to a vestibule with flanking rooms either side. From this vestibule you could access the courtyard, with the door normally positioned in the middle of one range. The main reception room was the triclinium or dining room. This was normally directly opposite the entrance. The triclinium could be the most lavishly decorated room of the building with as much money as possible spent on mosaic flooring and wall painting. Other rooms would include bedrooms, secondary dining rooms, kitchen and storerooms.

Preserving Zeugma for the future

Zeugma presented a unique challenge for archaeolgoists and conservators: as excavations started, the water level was continuously -if slowly- rising. While archaeological remains are in the ground they are in a stable environment; the moment they are excavated and exposed to the air a new equilibrium must be sought with the different environmental conditions, for example changes in humidity and temperature. Previous research at Zeugma predicted that fragile remains, like mosaics, frescoes and objects, were likely to be revealed, so conservation had to happen at the site to make sure that these specials finds would be rescued for research and public display. The conservators from the worked together with the archaeologists providing 'first aid' to consolidate and protect plasters, wall paintings, mosaics, and small finds.

However, an even more challenging aim of the project was to preserve the archaeological remains in situ so that they can be studied once the dam reservoir will be decommissioned in the future, with new technologies and methods. Conservators from the CCA worked with civil engineers to ensure that the archaeological remains will be safely preserved after they have been reburied. Wall paintings and some mosaics were consolidated, ancient cisterns and drains were backfilled with moist soil to protect against water erosion that might promote their eventual collapse. Once these conservation measures were completed, each excavation area was reburied even as work continue din other parts of the site. Eventually, the whole site was reburied with layers of damp soil and pebbles that are more resistant to water erosion.