The Uffington White Horse is the only hill-figure in Britain recorded in a variety of medieval documents.

Anglo-Saxon Charters

The Vale and the uplands to the north and south are well documented in Anglo-Saxon charters because much of the land belonged to major religious institutions such as Abingdon Abbey. Medieval monks were both literate and anxious to re-establish their legal ownership of land.

Charters are not maps. They are written descriptions, often in Old English, of the boundaries of estates (many of which coincide closely with later parishes). Today those estates still mark out the Vale and the Downs into long rectangular divisions – from water sources, across meadow, arable land, woodland and onto upland grazing. Each unit provides the resources needed for agriculture, flocks and herds. Hollow ways, eroded by centuries of use, link the Vale and the Downs.

A thousand years ago the parishes of Woolstone and Uffington were a single land unit known as AEscesbyrig – the Anglo-Saxon name of Uffington Castle. Perhaps this estate originated in prehistory when the first field systems were laid out, some defined by elongated boundaries.

In the mid-tenth century AEscesbyrig was divided into two smaller landholdings, Woolstone and Uffington – Wulfric's tun and Uffa’s tun. Wulfric was a powerful fellow, a thegn, who, in 960, held property across southern England. Uffa remains a mystery.

What is remarkable in the land charters is how often they rely on prehistoric barrows, hillforts or ancient ditches as landmarks: Rams Hill, a prehistoric enclosure, Wayland’s Smithy, the Ridgeway, Uffington Castle, Hod’s tumulus, Dragon Hill (known as Ecelesbeorh) are all mentioned – but not the White Horse.

So why not? Remember these charters are not a guide book. They serve the specific purpose of marking a line on the ground. And the western boundary of Uffington has a wealth of distinctive features on that line. The Horse lies off-line to the east and is redundant for the purposes of the surveyors.

Later documents

The clearest evidence for the Horse comes in documents after the Norman Conquest, in the records of Abingdon Abbey. A document of 1273 refers to ‘Le Whitchors’. In 1307 the village of Compton Beauchamp is named as Compton sub Album Equum (Compton under the White Horse). In 1348 we find Bishopstone super Album Equum.

A Wonder of Britain

The above references to the Horse are simply place-names. Perhaps more remarkable are documents listing the medieval ‘Wonders’ of Britain: De Mirabilibus Britanniae. In one list the Horse is placed fifth – an image ‘over which no grass grows’. Wishful thinking, perhaps, but this suggests the origin of the Horse was a mystery. In another manuscript the White Horse is listed second, after Stonehenge. Some historians have suggested that the ‘Wonders’ were first written down about 1100.

Guessing the Age of the Horse

With the growth of antiquarian studies, from the 17th century, people began to speculate about prehistory. There was not very much of it because theologians put the origins of the world at 4004 BC, a date established by James Usher, Archbishop of Armagh in 1645. To be precise, he supposed the Creation to have taken place at nightfall on 22 October. Usher’s talents should not be underestimated. He was a serious scholar using the evidence that was available to him.

Iron Age Coins

At about this time, John Aubrey was laying the foundations of the study of British prehistory, what he defined as ‘a wearisome task’. Nevertheless, he mentions that the Uffington White Horse resembles the segmented, beaked horse on a British coin found in Colchester.

In 1758, Anna Stukeley, daughter of the distinguished if eccentric antiquarian William, wrote to him after visiting the White Horse. She observed that it was ‘very much in the scheme of British horses on the reverse of their coins’. The coin images dated the birth of the Horse to the first century AD.

The Alfred Theory

However, despite the connection to the pre-Roman Conquest coins, the Iron Age theory did no catch on. Instead, the Reverend Francis Wise, the Radcliffe Library’s librarian, took himself off on a trip to White Horse Hill. He came back with a theory: everything he saw there was related to the Battle of Ashdown, a relatively minor battle involving pagan invaders, the Danes, the forces of King Aethelred and Wise’s hero, Alfred, the King’s brother.

Today historians dispute the location of the battle – it may have taken place along the Ridgeway but further to the east. The roles played by the King and his brother are also debated. But to Francis Wise all was clear: prehistoric hillforts were the camps of the rival forces, Wayland’s Smithy the burial place of the Danish leaders, and the White Horse a memorial of the Christian English victory. Evidence was there none. But never let the truth get in the way of a good story.

In the later 18th and 19th centuries, King Alfred had Greatness thrust upon him. He had saved and built the nation, was credited with founding Oxford University and the English navy, and promoting the Church. A statue to him still stands in the market place of Wantage, his birthplace, which lists his achievements. And because of the connection to him, the White Horse thrived in the sunshine of this English myth.

Changing Theories

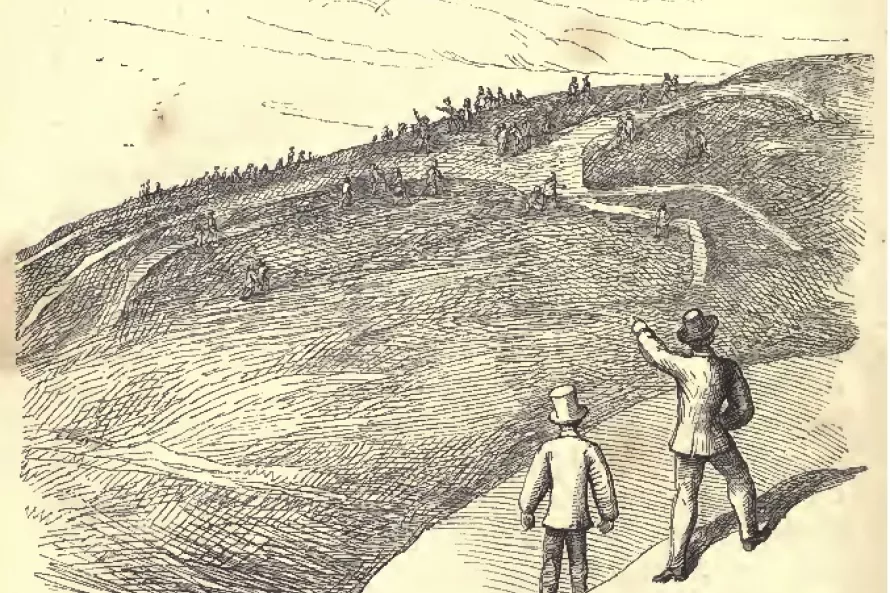

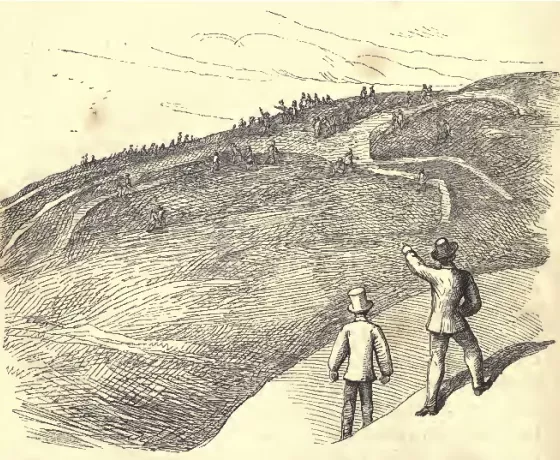

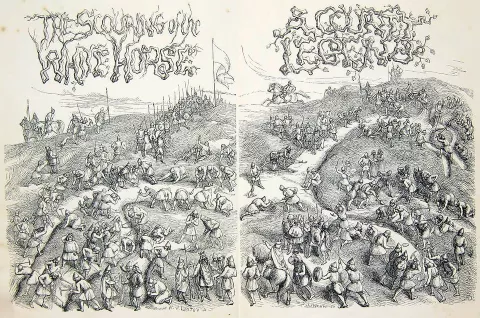

But spoilsports were on the march. As the study of antiquities became more academic, the evidence based on the observation of Iron Age coins was resurrected. Even Thomas Hughes, the author of the novel The Scouring of the White Horse (1859), eventually changed camps and shockingly admitted that the Alfred story was unlikely. In 1930 the final nail was hammered into that coffin by Stuart Piggott. As a young prehistorian, he wrote a fluent, well argued and ‘modern’ article entitled ‘The Uffington White Horse’ published in the then fashionable journal Antiquity. In it, he argued convincingly for a Late Iron Age date, again emphasising the stylistic similarity with some Iron Age coins.

Other Ideas

As Piggott's career and influence grew, he became one of the trinity of senior prehistorians – Graham Clark at Cambridge, Christopher Hawkes in Oxford, and Piggott himself of Edinburgh. Thanks to his reputation, the Late Iron Age Horse became generally accepted in the 20th century. Then a new challenger emerged, not an archaeologist but a student of folklore, Diana Woolner.

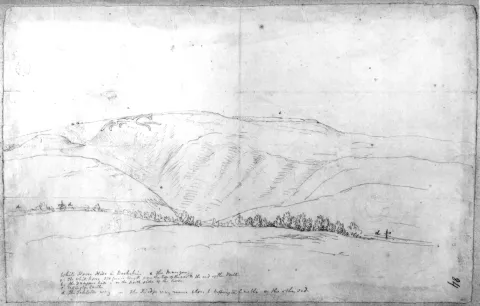

She wrote a couple of well-argued articles suggesting an early Anglo-Saxon origin for the Horse – after all Hengist and Horsa, the first invaders, were supposed to have planted their White Horse banner in Kent, where it still remains the county’s symbol. She challenged Piggott’s theory of a Celtic style horse. She claimed to be able to see a sturdier, more natural Horse in the turf. According to Ms Woolner, over generations the scourers had not done their job very well, and as a result we were left with the stylised version. Professor Hawkes in Oxford rather approved of the new theory, probably because it cocked a snook at his Edinburgh rival.

In 1949, historian Morris Marples published White Horses and Other Hill-figures, where he proposed a Bronze Age date for the White Horse, but was largely ignored.

So in the late 20th century there we stood. A White Horse that was certainly old. But how old? As a result of the uncertainty, the Uffington Horse remained in a kind of limbo. A famous icon but rarely discussed, or even mentioned, in text books on British prehistory; more likely to feature in books with titles such as Mysteries of Britain.